Introduction

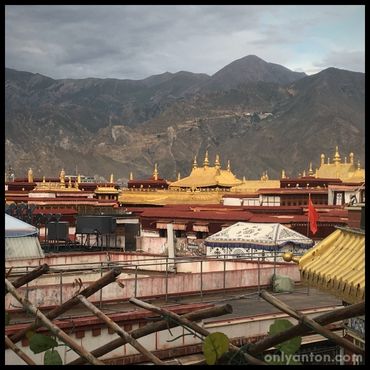

One of my fondest memories of the food of Tibet is sitting on a rooftop patio in Lhasa at the Tibetan Family Kitchen. I enjoyed a dish of Parmentier made with ground yak meat and yak cheese, accompanied by a cold Lhasa beer. The golden rooftops of the Jokhang Temple glimmered in the sunset, and the vibrant hum of Barkhor Street echoed below. That moment wasn’t just about the food. It was about experiencing the flavours, atmosphere, and traditions that define Tibetan culture.

The food of Tibet reflects the rugged landscape and resilient people who inhabit the region. At its core are simple, nourishing staples that offer warmth and sustenance in the high-altitude climate. Influences from Chinese, Nepalese, and Indian traditions bring added depth to Tibetan dishes. Each meal is a blend of local ingenuity and cross-cultural exchange. From butter tea to hearty stews and momos, Tibetan cuisine carries the spirit of a land shaped by mountains, monasteries, and a deeply spiritual way of life.

Purpose

The purpose of this blog post is to introduce you to some of the must-try foods in Lhasa. I’ll share some personal stories from my culinary adventures in the city. I’ll also provide cultural insights to help you engage with Tibetan food respectfully, adding depth to your experience beyond just the flavours on the plate.

In the sections that follow, we’ll explore staple dishes like tsampa and dhido, dairy products made from yak milk, traditional yak meat dishes, and a variety of local beverages. I’ll also offer some guidance on culturally respectful dining behaviour, ensuring you can appreciate Tibetan food in a way that honours local traditions. Whether you’re planning a trip to Lhasa or simply curious about Tibetan cuisine, this post will offer a window into a culinary world as unique as the landscape from which it springs.

Overview of the Food of Tibet

Tibetan cuisine is a product of geography, climate, and cultural exchange. The food is a reflection of the unique way of life in the high-altitude Himalayan region. With long winters and limited growing seasons, the food of Tibet emphasizes warmth, nourishment, and energy—qualities essential for survival in the mountains. Barley, especially in the form of tsampa (roasted barley flour), is a dietary cornerstone, providing vital sustenance. Yak dairy products—including butter, yogurt, and cheese—are equally indispensable, offering both nutrition and versatility. Meals are often hearty, with soups, stews, and dumplings bringing comfort in the cold climate.

Buddhism also shapes Tibetan dietary practices. Guided by compassion, many Tibetans limit meat consumption. Still, yak meat remains a crucial protein source, particularly in areas where fresh vegetables are scarce. Tibetan cuisine is about sustenance, community, ritual, and celebration. The Shoton Festival, for example, features sour yogurt as a symbolic food. Food in Tibet serves as a way to foster connection, marking both daily life and ceremonial occasions.

Cultural Influences

Tibet’s rich culinary traditions have been shaped by influences from neighbouring countries, especially China, Nepal, and India.

Chinese Influences

The proximity to Sichuan and Yunnan provinces has introduced bold spices, stir-frying techniques, and noodle dishes into Tibetan cuisine. Thukpa, a popular noodle soup, often includes Sichuan peppercorns and chilli oil, reflecting these shared culinary practices. Dumplings, or momos, echo Chinese jiaozi but feature local fillings such as yak meat. Pai huanggua (smashed cucumber salad), a refreshing dish with garlic and vinegar, is another example of Chinese influence. I discovered this dish during my time in Zhejiang province. Later, I enjoyed it again in Lhasa, where its cool crunch provided welcome relief after a long day of exploring.

Nepalese Influences

As a cultural bridge between Tibet and Nepal, Lhasa showcases many Nepalese dishes, such as spiced curries, lentil soups, and pickles. Nepalese-style momos—smaller and more delicately spiced than their Tibetan counterparts—are widely available. On cold days, earthy dishes like aloo dum (spicy potato stew) or gundruk (fermented greens) are perfect for warming up and reflect the influence of Nepalese home cooking.

Indian Influences

Indian culinary traditions have also made their way into Tibet through trade routes and migration. In Lhasa’s bustling markets, you can find spiced teas, fragrant curries, and even vendors selling samosas—a delightful reminder of India’s culinary presence. Masalas and lentil dals occasionally appear in Tibetan dishes, showcasing the diverse cultural connections that Tibet has cultivated over the centuries.

Tibetan cuisine balances tradition with innovation, blending local ingredients with techniques from its neighbours while maintaining its unique identity. Barley-based foods, yak dairy, and hearty meals remain the backbone of Tibetan cuisine. Culinary crossovers, though, enrich the dining experience, offering travellers familiar yet distinct flavours. Each dish tells a story of survival, connection, and cultural exchange. The food of Tibet is thus a gateway to a deeper understanding of the region’s history, landscape, and way of life.

Staples in Tibetan Cuisine

The region’s geography and climate have shaped the staple foods in Tibet. Hearty ingredients provide essential energy for life in the mountains. Although barley is central, other staples such as rice, noodles, and bread are also commonly enjoyed. The noodles found in thukpa or thenthuk offer warmth and comfort. Flatbreads provide a portable meal for travellers. These Tibetan food staples reflect the necessity of sustenance over extravagance, balancing simplicity with cultural meaning.

Tsampa: The Heart of Tibetan Cuisine

Tsampa is one of the most essential foods in Tibetan culture. It is made from roasted barley flour, which provides both nutrition and warmth. Its simplicity and versatility make it a cornerstone of Tibetan meals. Traditionally, tsampa is mixed with butter tea or broth to create a smooth, dough-like consistency. One can roll it into small balls and eat it by hand to provide a quick, energy-packed snack. Tsampa is also portable and non-perishable, which is ideal for nomadic lifestyles or long journeys.

Beyond everyday use, tsampa has ritual significance. It is used in Buddhist ceremonies, where offerings of tsampa are thrown into the air as a gesture of prayer and goodwill. Tsampa also symbolizes community and connection—sharing it is an act of hospitality and respect.

During my trek to Everest Base Camp, I had the chance to experience tsampa in its most authentic form. After settling into a small hut, a local man prepared tsampa. He mixed roasted buckwheat flour with butter tea, kneaded it into a dough and offered it to me. The simplicity of the meal—a staple of Tibetan life—felt profound. Seated by a yak dung fire, I shared this humble breakfast in silence with the locals. It was a moment that transcended language and underscored the meaningful connection that food can foster across cultures.

Dhido: A Close Cousin to Tsampa

Like tsampa, dhido is another essential dish made from barley or buckwheat flour. However, it has a different preparation and texture. Unlike tsampa, which is often mixed with tea, dhido is combined with water. The result is a dense, smooth dough with a consistency closer to polenta. Dhido is typically served with side dishes, such as pickles or dried meat, making it more of an accompaniment than a standalone meal.

Although tsampa and dhido share similar ingredients, their textures and uses set them apart. When prepared, tsampa has a crumbly dough-like consistency, making it easy to shape into balls. Dhido, meanwhile, is thicker and smoother. It is served in a communal dish alongside flavourful accompaniments. Tsampa is a daily staple, eaten throughout the day in various forms, while dhido is often served at meal times and as a side dish.

Nonetheless, both of these traditional foods are testaments to Tibetan ingenuity. These foods express a deep understanding of how to thrive in challenging environments. Whether eating tsampa in a hut by a yak dung fire or dhido with a spicy pickle, these staples offer sustenance and connection, tradition, and meaning in Tibetan culture.

Tibetan Comfort Foods

When it comes to Tibetan cuisine, a few dishes stand out as essentials of both everyday life and special occasions. Among the most beloved dishes are momos, thukpa, and thenthuk. These iconic foods offer a taste of the region’s culinary heart and cultural significance.

Momos

Momos are steamed or fried dumplings filled with various ingredients like meat, vegetables, or yak cheese. They are typically served with a spicy chilli powder or sauce for dipping, adding a flavorful kick. A popular street food and a dish often shared during festivals and gatherings, momos hold a special place in Tibetan culture. These delicious dumplings are more than just food—they represent hospitality and celebration, often bringing people together.

If you find yourself in Lhasa, I recommend trying momos at Tibetan Family Kitchen, a cozy rooftop restaurant near the Jokhang Temple. The view and ambiance enhance the experience. You can also explore local eateries along Barkhor Street, where vendors serve momos fresh off the steamer.

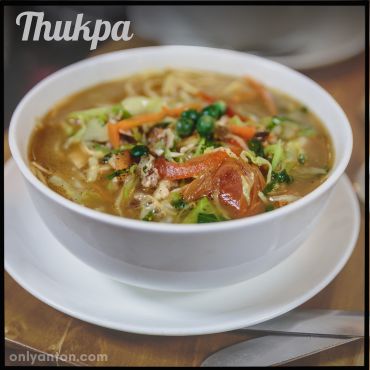

Thukpa

Thukpa is a hearty noodle soup, traditionally made with broth, meat (such as yak or beef), and vegetables. This dish is perfect for cold Tibetan nights, offering warmth and sustenance. Regional variations abound, with some versions including spicier broths or additional vegetables, reflecting local tastes and ingredients.

I vividly remember enjoying a steaming bowl of thukpa after a long day of pilgrimage to witness the Thangka unveiling at Drepung Monastery. The warm broth and noodles provided welcome comfort after hours of walking. The simplicity of the dish seemed to embody the spirit of Tibetan hospitality.

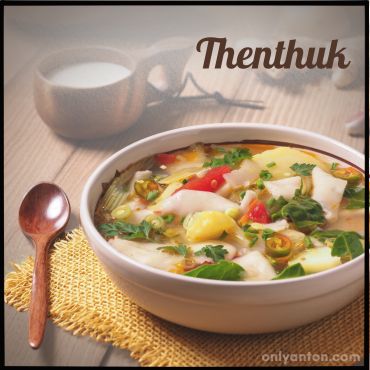

Thenthuk

Thenthuk, another famous Tibetan soup, is known for its hand-pulled noodles. Unlike the thinner noodles of thukpa, the noodles of thenthuk feature thicker, broader strips of dough, lending the dish a more substantial texture. Like thukpa, it typically contains meat, vegetables, and broth, but the distinct noodle preparation sets it apart.

Thenthuk’s rustic preparation reflects the practicality of Tibetan cuisine, using ingredients readily available in the highlands. This dish is often prepared at home during winter. It is a perfect meal for travellers looking to experience something both filling and deeply rooted in Tibetan culinary tradition.

From the festive momos to the comforting thukpa or the hearty thenthuk, these dishes represent Tibetan flavours and the hospitality and warmth of the people who serve them.

Yak Dairy: A Pillar of Tibetan Cuisine

The yak plays a crucial role in Tibetan life, providing labour, meat, wool, and dairy products. Interestingly, the term “yak” refers only to the male. The female is called a dri, though many outside Tibet use “yak” to refer to both. In the Tibetan diet, dairy from yaks (dris) is central, supplying milk, butter, yogurt, and cheese. This reliance on dairy is unusual within the broader Chinese culinary tradition, which generally does not emphasize dairy products. A notable exception is Yunnan, where cheese also appears in regional dishes. Yak butter even finds its way into religious rituals. Yak butter candles, for instance, illuminate the halls of many Tibetan temples and monasteries.

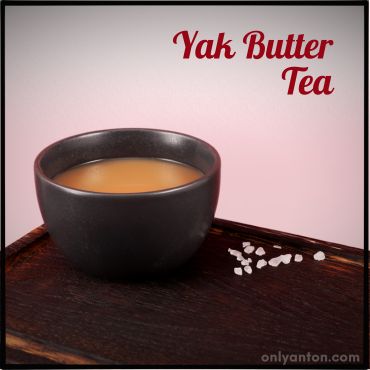

Po Cha (Butter Tea)

A staple of Tibetan life, butter tea (po cha) is made from yak butter, salt, tea leaves, and water. The ingredients are churned together to form a thick, salty brew with a distinctive flavour. Butter tea is more than just a beverage; it is a daily constant in Tibetan households, symbolizing hospitality and warmth. Offering butter tea to guests is a traditional gesture of welcome, and it is often served throughout the day.

Butter tea serves another important functional purpose. It helps combat the cold and high-altitude conditions of the Tibetan plateau, providing both hydration and necessary calories. The salt helps maintain electrolyte balance, while the fats from yak butter provide energy and warmth. Many travellers will not be accustomed to the unique flavour and aroma. Butter tea can be an acquired taste, yet it is a must-try cultural experience in Tibet.

Sour Yak Yoghurt

Another essential dairy product in Tibetan cuisine is sour yak yoghurt, which plays a pivotal role in the Shoton Festival. The festival, known as the Yogurt Banquet Festival, celebrates both religion and the arts. Tibetan monks traditionally break their summer retreat with bowls of sour yogurt, which is also offered to guests.

This fermented yogurt has a tart and refreshing flavour, making it a favourite snack during the warmer months. The fermentation process does more than preserve the milk. It also enhances the nutritional value and contributes beneficial probiotics to the Tibetan diet. Fermented foods like yoghurt reflect the practicality of Tibetan cuisine. Such products place an emphasis on the preservation and health benefits in an environment where fresh food can be scarce.

Yak Cheese and Churpi (Durkha)

There are various forms of yak cheese, from soft curds to hard, dried chunks. Among the most notable varieties is churpi (also called durkha). It is a hard, chewy cheese popular with locals and travellers alike. Churpi is often sold attached to strands of yak wool or hair, offering a rustic snack for those on the go.

I had the chance to try churpi during my trek from Lhasa to Everest Base Camp. My guide handed me a small piece of this curious cheese, white and chalky in appearance, with a strand of wool attached. When I placed it in my mouth, I quickly realized how unforgivingly hard it was—nearly impossible to bite or chew. Instead, one is supposed to suck on the cheese, allowing it to soften slowly over time. Despite my best efforts, the chunk remained solid throughout. The flavour was complex and earthy, with notes of milk, grass, and a faint hint of dung, likely from the wool. Churpi’s toughness is part of its charm and practicality—it lasts a long time and provides sustenance on long journeys through the mountains.

Yak cheese also holds cultural significance as part of rituals and festivals. As with other dairy products, its importance reflects the resilience of Tibetan culture and the close relationship between the people, the land, and their livestock. Yak dairy products thus embody the essence of Tibetan life: practical, nourishing, and deeply intertwined with tradition.

Tibetan Yak Meat: A Hearty Protein

In Tibet’s high altitude and harsh climate, yak meat is yet another food that provides nourishment and warmth. With its lean texture and slightly gamey flavour, yak meat is the primary protein source in many Tibetan dishes. Rich in nutrients and low in fat, yak meat is ideally suited to sustain the body through Tibet’s cold and rugged environment.

Hearty Yak Stew, Dumplings, and Jerky

Yak meat forms the backbone of several Tibetan dishes designed to combat the cold climate. One popular preparation is yak stew, a rich and savoury dish made with chunks of yak meat, potatoes, onions, and other root vegetables. The stew is slowly simmered to tenderize the meat, creating a comforting meal that is perfect after a long day of trekking in the mountains.

Another beloved dish is yak dumplings, which are similar to momos but filled with ground yak meat. These dumplings may be steamed, boiled, or fried. They are usually served with spicy dipping sauces, offering a satisfying snack or light meal. Yak dumplings are commonplace during festivals and celebrations, underscoring their importance in Tibetan culinary traditions.

For those on the go, yak jerky offers a convenient and long-lasting source of protein. The meat is dried and preserved with salt and spices, making it an ideal travel food for long journeys across the Tibetan plateau. While it can be tough and chewy, yak jerky provides a tangible taste of Tibetan life on the move, sustaining travellers and locals alike.

Shab Tra: Grilled Yak Skewers

One of the more festive ways to enjoy yak meat is through shab tra, a popular street food in Tibet. Shab tra consists of grilled skewers of yak meat, often marinated with spices and herbs to enhance its flavour. Some versions of shab tra feature other meats or a combination of vegetables, but yak remains the star ingredient.

Grilled yak skewers are typically enjoyed as a snack or casual meal during social gatherings, often accompanied by chhaang (Tibetan barley beer) or tea. The spices used in shab tra vary by region, but the result is always a smoky, savoury delight that embodies the bold flavours of Tibetan cuisine.

A Personal Experience: Parmentier with Yak Meat and Yak Cheese

During my time in Lhasa, I had the opportunity to enjoy a unique fusion dish that blended Western cooking techniques with Tibetan ingredients. At a small restaurant called Tibetan Family Kitchen, located just off the bustling Barkhor Street near the Jokhang Temple, I discovered a dish that felt both familiar and exotic: Parmentier with Yak Meat and Yak Cheese.

Parmentier is typically a French dish, somewhat akin to shepherd’s pie, featuring seasoned ground meat topped with creamy mashed potatoes. The version I enjoyed in Lhasa, however, had been given a distinctively Tibetan twist. The dish was prepared with ground yak meat, seasoned with spices, and topped with rich, melted yak cheese. The flavours were bold and satisfying. The yak meat provided a unique depth of taste that was complemented by the creamy texture of the cheese.

I savoured this dish on the restaurant’s small rooftop patio, overlooking the golden rooftops of the Jokhang Temple. I sipped a cold Lhasa beer as the sun set, casting a warm glow over the surrounding buildings and the lively streets below. The combination of delicious food, refreshing beer, and a magical view made it one of the most memorable meals of my travels.

Yak meat, in its many forms—from simple jerky to elaborate Parmentier—epitomizes the resourcefulness and creativity of Tibetan cuisine. In all its variations, yak meat reflects the spirit of the Tibetan people: resilient, inventive, and deeply connected to the land they call home.

Tibetan Alcohol

Beyond food, beverages also play an essential role in Tibetan culture, offering warmth, celebration, and moments of shared connection. While yak butter tea is the most iconic drink, other beverages, such as chhaang and Lhasa Beer, provide unique tastes of the Tibetan experience.

Chhaang: The Festive Barley Beer

Chhaang is a traditional Tibetan fermented barley beer enjoyed during festivals, celebrations, and social gatherings. Slightly cloudy and mildly sour, chhaang is often served at room temperature or warm, which makes it particularly comforting in Tibet’s cold climate. It has a relatively low alcohol content, but its strength can vary based on how long it ferments.

The brewing process for chhaang involves fermenting barley grains (sometimes mixed with other grains like rice or millet) with a starter culture. The resulting drink has a light, refreshing taste with a hint of tartness from the fermentation. At festivals and gatherings, it is served in ceramic or wooden bowls. Chhaang is often accompanied by songs, dances, and laughter that foster a sense of community and celebration. In Tibetan culture, it is considered courteous to accept chhaang when offered, especially during festive occasions.

Lhasa Beer: A Modern Refreshment

In addition to chhaang, Tibet offers a more modern beverage option with Lhasa Beer—a popular local brew that has found favour among locals and tourists. Known for its light and crisp taste, Lhasa Beer is brewed with Himalayan spring water, barley, and hops, giving it a clean, refreshing flavour that pairs perfectly with the substantial dishes of Tibetan cuisine.

Lhasa Beer is widely available throughout Lhasa, from rooftop cafés and local bars to restaurants catering to travellers. It offers a pleasant way to wind down after a day of exploring. The earthy warmth of Chhaang and the crisp refreshment of Lhasa Beer reflect the tradition and modernity of Tibetan life, offering visitors a chance to raise a glass to the spirit of the Himalayas.

Honouring Tibetan Food Traditions

Dining in Tibet is not just about nourishment. It’s also a cultural exchange that reflects centuries-old traditions. Being mindful of local customs while eating is a meaningful way to show respect for Tibetan culture and enhance your travel experience. Here are a few key aspects of dining etiquette, customs, and respectful behaviour to remember.

Dining Etiquette

In Tibetan culture, it is customary to accept food or drink with both hands as a gesture of gratitude and respect. When offered tea or food, wait for the host to serve you rather than help yourself. It’s also important to avoid wasting food, as every bite is considered valuable—especially in high-altitude regions where food is not always easy to come by.

Customs at the Table

While it is polite to taste everything offered, it is perfectly acceptable to decline a second helping if you are full. A subtle gesture, such as placing your hand over your cup or bowl, signals to your host that you’ve had enough. Sharing meals is also a communal act in Tibetan culture. It’s common to see dishes placed at the center of the table for everyone to enjoy.

Respect for Local Traditions

Refrain from criticizing or making negative remarks about unfamiliar dishes or eating practices, even if the flavours or textures surprise you. Tibetan food, like butter tea or dried yak cheese, may take some getting used to, but showing respect for these traditions is essential. A positive and open attitude towards the unfamiliar is highly valued.

Personal Tip: Follow the Locals’ Lead

One of the best ways to show respect while dining in Tibet is by observing how locals behave. If unsure how to act, watch what others do—from how they receive tea to how they pace their meal. Adapting to these customs shows respect and helps you connect more authentically with the people and culture.

You’ll gain a deeper appreciation for Tibetan hospitality by dining with mindfulness and an open heart. Each meal becomes more than just a culinary experience—it becomes a cultural encounter.

Conclusion

Tibetan cuisine reflects the region’s unique geography, cultural heritage, and way of life. From the nourishing warmth of yak butter tea to the savoury delights of momos and hearty yak stew, each dish carries its own story—one rooted in tradition and adapted to the high-altitude environment. The variety of flavours, textures, and preparations in Tibetan food showcases the interplay between simplicity and richness, with influences from China, Nepal, and India enhancing the local fare.

Exploring Tibetan cuisine offers more than satisfying meals. It provides a gateway to deeper cultural understanding. Through food, travellers can connect with the warmth of Tibetan hospitality, partake in ancient customs, and gain insights into the values that shape daily life in Tibet. No matter if you are in Lhasa or at a local Tibetan restaurant in your hometown, embracing these culinary experiences can open doors to meaningful cultural encounters.

What About You?

What Tibetan dish has captured your heart (or curiosity)? Have you had a memorable food experience in Tibet or tried any Tibetan dishes closer to home? We’d love to hear about your favourite dishes, surprising flavours, or moments shared around a Tibetan meal.

If you haven’t yet sampled Tibetan food, why not seek out a local eatery and give it a try? Share your thoughts in the comments section and engage with the Only Anton community. We’d love to explore Tibetan cuisine with you! Let’s continue the conversation about travel, culture, and food, one dish at a time.

Further Reading and Resources

These resources offer further insights into the unique blend of tradition, spirituality, and practicality that defines Tibetan cuisine and culture.

Related Posts on Only Anton

- The Shoton Festival and Thangka Pilgrimage in Lhasa: Experience the Shoton Festival and the Thangka Pilgrimage in Lhasa, Tibet, and discover the spirituality of this unique celebration.

- The Trek to Everest Base Camp: Join a trek to Everest Base Camp that transcends physical travel, exploring deep cultural insights and personal transformation.

- The Eight Great Tastes of Chinese Cuisine: Learn about the Eight Great Tastes of Chinese Cuisine, their cultural significance, and how balance in flavour creates harmony in dishes.

Books

- Tibetan Cooking: Recipes for Daily Living, Celebration, and Ceremony by Elizabeth Kelly (2007): A practical guide to preparing authentic Tibetan dishes with insights into Tibetan food culture. Borrow it from a library, read it online, or get your own copy here.

- Taste Tibet: Family Recipes from the Himalayas by Julie Kleeman and Yeshi Jampa (2022) – A beautifully illustrated cookbook featuring traditional Tibetan recipes alongside personal stories, capturing the heart of Himalayan home cooking. Find it at a local library, online, or for sale here.

- In Buddha’s Kitchen: Cooking, Being Cooked, and Other Adventures by Kimberley Snow (2004) – A memoir blending stories of spiritual growth, monastic life, and Tibetan cuisine, offering personal insights through the lens of food. Look for it online, at a library, or get your copy here.

Articles and Websites

- BBC Magazine, “Comfort Food in the Harshest Climate” by Nyima Pratten and Daniel Agha-Rafei (August 2019): An exploration of how Tibetan food sustains people through harsh climates, focusing on local dishes and the cultural significance of comfort food. Read the article here.

- Chhaang, Wikipedia: An overview of chhaang, a traditional Tibetan alcoholic beverage made from fermented barley, often enjoyed during festivals and social gatherings. Find the entry here.

- List of Tibetan Dishes, Wikipedia: A comprehensive list of traditional Tibetan foods, including staples, beverages, and regional specialties, reflecting the variety and richness of Tibetan cuisine. Read the entry here.