Part Five of the Mastering Art Appreciation: From Novice to Connoisseur series

Section I: Introduction

Symbolism and iconography unlock hidden meanings in art, revealing layers of narrative and intent beneath the surface. Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Netherlandish Proverbs (1559) exemplifies this concept in spectacular fashion. At first glance, the painting appears to depict a lively village scene bustling with activity. However, a closer inspection reveals it to be a “visual encyclopedia” of human folly, illustrating more than 100 proverbs and idioms—many of which remain familiar even today.

From the timeless “To bang one’s head against the wall” to the less familiar “The herring does not fry here,” each vignette offers a glimpse into the social norms, wisdom, and absurdities of 16th-century Lowlands culture. Bruegel’s ability to encode these sayings into everyday scenes elevates his work from mere narrative to a profound commentary on human behaviour. Through this, the painting exemplifies the power of symbols to transcend time and communicate universal truths.

This post is the fifth installment in the Mastering Art Appreciation: From Novice to Connoisseur series. It is designed as a guide to the “hidden language” of art, helping you uncover the layers of meaning embedded in paintings, sculptures, and other visual media.

In the sections that follow, we’ll explore the role of symbolism in art, delve into common themes and motifs, and analyze iconic works from various periods and styles. Along the way, you’ll gain practical tips for interpreting symbols, enhancing your understanding and enjoyment of art. As with Netherlandish Proverbs, you’ll discover that every detail—no matter how small—can carry profound meaning.

Section II: The Role of Symbolism in Art

Symbolism in art is the language through which artists communicate ideas, emotions, and narratives that transcend the immediate visual. By embedding symbols—whether overt or subtle—into their work, artists create a bridge between their intent and the viewer’s interpretation. Iconography, the study of symbols and their meanings within specific cultural or historical contexts, is integral to unlocking this hidden language, providing deeper insights into the stories that artworks tell.

Types of Symbols: Overt and Hidden

Symbols in art can range from direct and universally recognized to subtle and layered with context.

Overt Symbols

Overt symbols are explicit and widely understood across cultures or within a specific tradition. They often convey clear meanings without requiring extensive interpretation. For instance, in Andrea Mantegna’s Saint Sebastian (1457–58), the arrows piercing the saint’s body are overt symbols of his martyrdom and unwavering faith. Similarly, halos in religious art signify sanctity, while skulls universally represent mortality.

Subtle or Hidden Symbols

In contrast, subtle or hidden symbols demand deeper knowledge of cultural, historical, or personal context. Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait (1434) exemplifies this complexity: the single candle burning in the chandelier represents the eye of God, and the small dog at the couple’s feet symbolizes fidelity. Without an understanding of 15th-century symbolism, these details might be overlooked or misunderstood.

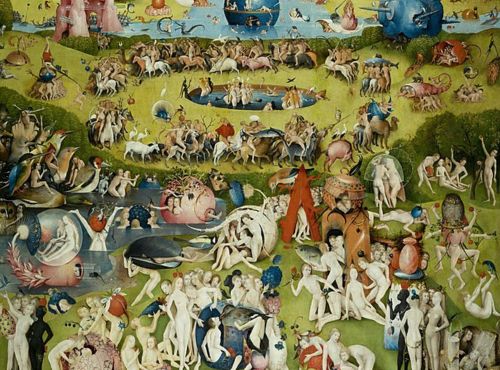

Another example is the owl in Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights (1490–1510). Often associated with wisdom, the owl here represents folly or moral blindness, a shift rooted in the painting’s allegorical framework. Such layered meanings challenge the viewer to look beyond the surface.

Symbolism vs. Presentation: Illustrative Depiction and Beyond

Art can serve as both an illustrative presentation of a subject and a symbolic exploration of deeper meanings. Understanding this distinction is crucial for art appreciation.

Illustrative Depiction

Works like Winslow Homer’s The Gulf Stream (1899) portray danger through a direct and descriptive lens. The shark circling the wrecked boat is an illustrative example of peril, emphasizing narrative clarity. Similarly, Jacques-Louis David’s The Death of Marat (1793) presents a historical event, offering a straightforward account of Marat’s assassination.

Symbolism

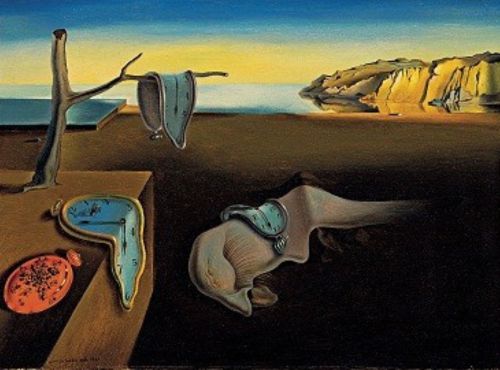

In contrast, symbolic works transcend mere depiction to evoke abstract ideas or emotions. Salvador Dalí’s The Persistence of Memory (1931) transforms melting clocks into metaphors for the fluidity and fragility of time. In this context, the shark from Homer’s painting, if placed in a surrealist composition, could symbolize subconscious fears or primal instincts rather than literal danger.

The boundary between presentation and symbolism often overlaps. While The Death of Marat is primarily illustrative, it also carries symbolic weight in its revolutionary context. Marat’s limp hand and serene expression evoke martyrdom, casting him as a Christ-like figure of sacrifice for the cause.

Cultural and Temporal Context

The meaning of symbols is not static. It evolves across cultures and epochs, shaped by historical, religious, and societal influences. A symbol’s significance in one context may differ dramatically in another. For instance, the lily, commonly associated with purity in Christian iconography, might symbolize death or renewal in other traditions.

Understanding a work’s cultural and temporal context is essential for accurately interpreting its symbols. Analyzing Andrea Mantegna’s Saint Sebastian requires knowledge of Renaissance Christian martyrdom narratives. Meanwhile, understanding Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights benefits from familiarity with late medieval eschatological concerns.

By recognizing the dynamic nature of symbols and their connection to their time and place, viewers can deepen their engagement with art, uncovering layers of meaning that might otherwise remain hidden.

Section III: Common Symbolic Themes and Motifs

Symbols in art provide layers of meaning, inviting viewers to look beyond the surface. Recognizing recurring themes and motifs can uncover stories, emotions, and philosophies embedded in artworks. This section explores four major symbolic categories: nature, religion, mortality, and modern secular motifs.

A. Nature

The natural world has long served as a repository of symbolism, reflecting human emotions, beliefs, and societal values.

Flowers

Flowers are among the most potent natural symbols, each species carrying distinct meanings. In Stefan Lochner’s Virgin of the Rose Garden (c. 1440), roses symbolize purity and sacrifice, often associated with the Virgin Mary in Christian iconography. Lilies, common in Annunciation scenes, signify purity but can also represent death, as seen in funeral arrangements. The “language of flowers,” or floriography, imbues botanical details with cultural and emotional resonance.

Animals

Animals, too, appear as symbols of virtues, vices, and spiritual ideas. In The Arnolfini Portrait (1434), the dog at the couple’s feet represents loyalty and fidelity. Rabbits are fertility symbols, while lambs and fish often represent Christ in Christian art. Birds, such as peacocks, symbolize immortality, while doves signify the Holy Spirit. Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights (1490–1510) complicates these associations: an owl, often linked to wisdom, instead represents folly and moral blindness within the work’s chaotic allegory.

Practical Tip:

When analyzing natural motifs, consider both the species and its placement. A single flower in a vase may signify life’s fragility, while an entire garden could evoke paradise or abundance.

B. Religion

Religious iconography encodes stories, virtues, and spiritual truths in visual form, requiring knowledge of cultural and historical contexts to interpret fully.

Iconography of Saints and Martyrs

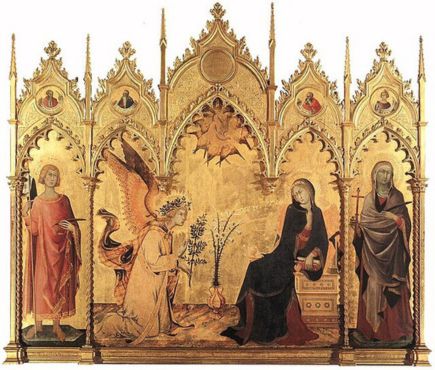

Saints are frequently identified by their unique symbols. The Four Evangelists, for example, are paired with specific creatures: Matthew with a winged man, Mark with a lion, Luke with a bull, and John with an eagle. Saint Sebastian’s arrows symbolize martyrdom, while Saint Lucy’s eyes on a golden plate denote her suffering and sanctity. Simone Martini and Lippo Memmi’s Annunciation with Saint Margaret and Saint Ansanus (1333) features rich saintly iconography, blending spiritual and artistic brilliance.

Biblical Themes in Genre Paintings

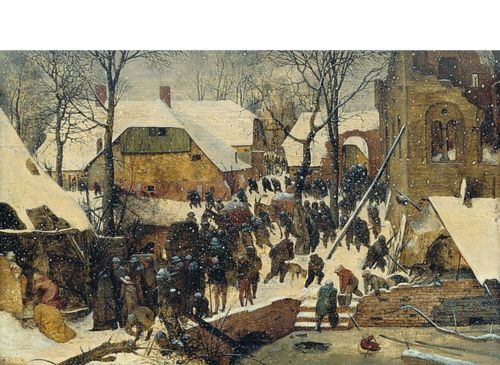

Religious themes often blend into everyday life in works like Pieter Brueghel’s The Procession to Calvary or Adoration of the Magi in the Snow (1563). These paintings weave sacred narratives into familiar settings, merging devotion with cultural context.

Buddhist and Eastern Iconography

Eastern art offers its own symbolic language. In Hokusai’s The Great Wave off Kanagawa (1831), the towering wave represents nature’s overwhelming power, a nod to the Buddhist concept of impermanence.

Practical Tip:

Cross-reference religious texts or museum plaques to decipher symbols in sacred art. Understanding theological underpinnings enriches the viewing experience.

C. Mortality and Vanitas

Art often confronts life’s transience, reminding viewers of mortality through potent symbols.

Vanitas Still Life Dutch still-life paintings use decaying or consumed objects as memento mori. In Willem Claeszoon Heda’s Still-life with a Gilt Cup (1635), the peeled lemon and half-empty goblet are visual metaphors for life’s ephemerality.

Decay and Death

The Portrait of a Woman of the Hofer Family (c. 1470) includes a fly on the woman’s wimple, a subtle yet striking reminder of human mortality. Such symbols prompt reflection on life’s fleeting nature and moral purpose.

Practical Tip:

Look for signs of decay or incompleteness, such as wilting flowers or unfinished meals, as clues to more profound moral or philosophical messages.

D. Modern and Secular Symbols

Modern and contemporary art often turns to secular or abstract themes, reimagining traditional symbols and creating new ones that reflect the concerns of their time. By adapting or subverting established iconography, these works engage with themes of identity, politics, and societal transformation.

Cultural Symbols

Frida Kahlo’s The Two Fridas (1939) is a deeply personal exploration of identity, pain, and duality. The two figures—one dressed in traditional Mexican attire, the other in European-style clothing—represent Kahlo’s mestiza heritage and emotional turmoil. The exposed heart, veins, and surgical instruments allude to her physical suffering following multiple surgeries and miscarriages, while the blood-stained scissors symbolize the fragility of her connections. Kahlo’s symbolic language blurs the line between autobiography and universal human themes, making her work both intimate and politically charged.

Political Symbols

Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa (1818–1819) offers a powerful allegory of human suffering and political critique. The painting depicts the aftermath of a real-life shipwreck, where survivors endured starvation and desperation. Beyond its harrowing narrative, the work symbolizes the failures of leadership and the vulnerability of the human condition. The contrasting light and dark tones reflect the tension between hope and despair, while the pyramid-like arrangement of figures suggests both solidarity and the precariousness of survival. Géricault’s choice to highlight the human cost of political incompetence transforms the painting into a timeless critique of authority and societal neglect.

Surrealist Symbols

Salvador Dalí’s The Persistence of Memory (1931) embodies the dreamlike quality of Surrealism through its symbolic use of everyday objects. The melting clocks evoke the fluidity and impermanence of time, challenging conventional notions of linearity and reality. Meanwhile, the ants crawling on one of the clocks symbolize death and decay, adding a layer of existential unease. The barren landscape, reminiscent of Dalí’s native Catalonia, grounds these surreal symbols in a personal yet universal meditation on the subconscious, memory, and the passage of time.

Modern or Contemporary Symbols

Yang Yongliang’s View of Tide (2008) offers a striking fusion of tradition and modernity, critiquing contemporary environmental issues. At first glance, this inkjet print resembles a serene Chinese shanshui (“mountain-water”) landscape painting with mist-shrouded mountains and tranquil waters. On closer inspection, the “mountains” are clusters of densely packed high-rise buildings, while the “trees” are revealed as construction cranes and hydroelectric towers. By subverting the traditional aesthetic, Yongliang exposes the environmental and cultural costs of rapid urbanization. His work speaks to the global tension between development and sustainability, urging viewers to question the impact of modern progress on the natural world.

Practical Tip

Modern and contemporary symbols often reflect the cultural and historical moment in which they are created. When engaging with these works, consider the artist’s personal experiences, the political climate, and the cultural shifts that may have influenced their symbolism. Understanding these contexts can help decode the nuanced messages embedded in the art, revealing connections between personal, cultural, and global narratives.

Section IV: Analyzing Symbols in Famous Works

Symbols in art deepen the narrative, emotional, and philosophical dimensions of a work. By examining iconic paintings, viewers can see how symbols are woven into compositions to communicate nuanced meanings. This section provides an in-depth analysis of five selected masterpieces, highlighting their symbolic layers and artistic intentions.

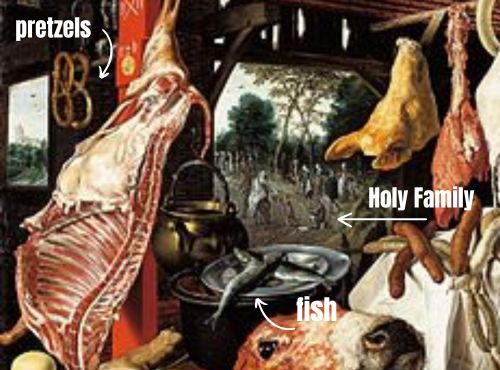

A. Pieter Aertsen, A Meat Stall with the Holy Family Giving Alms (1551)

At first glance, Aertsen’s A Meat Stall appears to be a vibrant still life celebrating abundance. The foreground is dominated by an array of meats and produce, meticulously rendered to emphasize their texture and weight. However, the inclusion of the Holy Family in the background transforms the work into a moral and religious allegory.

- Symbols of Decay and Charity: The contrast between the Holy Family’s modest act of giving alms and the foreground’s excess highlights a duality: spiritual humility versus material indulgence. The fish and pretzels, symbols of Lent and Christian charity, are subtly placed amidst the carnage of butchered meat, suggesting the tension between sacred and profane.

- Juxtaposition and Composition: The visual prominence of worldly goods over the subdued religious scene invites viewers to reflect on misplaced priorities, urging a return to spiritual values.

- Interpretation Tip: Pay attention to the placement and emphasis of symbols within the composition, as they often guide the moral or narrative thrust of the work.

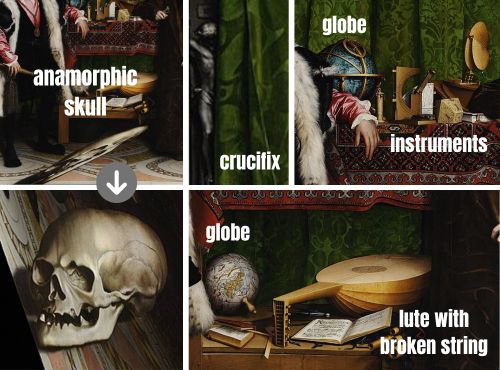

B. Hans Holbein the Younger, The Ambassadors (1533)

Holbein’s The Ambassadors is a masterclass in layered symbolism, intertwining Renaissance ideals of worldly achievement with the inevitability of death and the tension between earthly pursuits and spiritual salvation.

- Worldly Knowledge and Mortality: The meticulously rendered objects scattered across the table—celestial and terrestrial globes, a quadrant, a lute with a broken string, and mathematical instruments—symbolize human curiosity, exploration, and the intellectual achievements of the Renaissance. Yet, this celebration of worldly knowledge is profoundly undercut by the distorted anamorphic skull in the foreground. When viewed head-on, the skull appears abstract and meaningless, but from a specific angle, it emerges as a stark reminder of mortality. This duality invites viewers to shift their physical and intellectual perspectives, underscoring the precarious balance between life’s transience and human ambition.

- Religious Allusions: Holbein carefully embeds religious references to highlight the tension between material success and spiritual salvation. The partially obscured crucifix in the upper left corner is a subtle yet powerful reminder of faith and redemption. Similarly, the lute’s broken string may symbolize discord or the fragility of life, suggesting that even harmony and beauty are fleeting without spiritual grounding.

- Symbolism of Perspective: The skull’s anamorphic distortion exemplifies how perspective shapes meaning, both visually and conceptually. This technique forces viewers to confront the painting from multiple angles, reinforcing the idea that understanding often requires a shift in viewpoint.

- Interpretation Tip: When examining works like The Ambassadors, look for visual elements that challenge the initial impression or disrupt the scene’s apparent harmony. Such details often signal deeper, layered meanings. Here, the juxtaposition of opulence and decay invites viewers to reflect on their own priorities and the impermanence of worldly pursuits.

C. Gustave Moreau, Oedipus and the Sphinx (1864)

Moreau’s painting captures a pivotal mythological moment while infusing it with the dreamlike qualities of the Symbolist movement.

- Symbolist Aesthetic: The Sphinx, perched menacingly, embodies the femme fatale archetype, her enigmatic presence reflecting the psychological and existential struggles of Oedipus. Their locked gaze suggests a mirroring of inner worlds—a confrontation not just with a riddle but with one’s identity and fate.

- Archaic and Spiritual Influences: The archaic style of the painting, with its intricate details and rich colour palette, underscores the Symbolist desire to transcend realism, focusing instead on emotion, imagination, and spirituality.

- Interpretation Tip: Consider the interplay between mythological subject matter and personal or universal themes. The symbolic resonance of the figures often lies in their archetypal qualities.

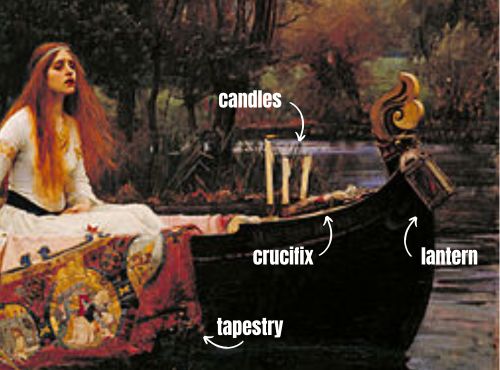

D. John William Waterhouse, The Lady of Shalott (1888)

Drawing inspiration from Tennyson’s poem, Waterhouse’s The Lady of Shalott combines literary and visual symbolism to evoke themes of isolation, destiny, and mortality.

- Symbols of Mortality and Faith: The extinguished candles, the crucifix, and the lantern on the boat each carry symbolic weight. The three candles, two of which are already extinguished, signify life’s fragility, while the crucifix represents faith as a guiding light in darkness.

- Pre-Raphaelite Ideals: Waterhouse’s meticulous attention to detail and vibrant colour palette echo the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood’s reverence for Quattrocento art, enhancing the painting’s symbolic and emotional depth.

- Interpretation Tip: Explore the relationship between literary and visual elements. The symbolism often extends beyond the canvas, drawing on cultural or narrative contexts.

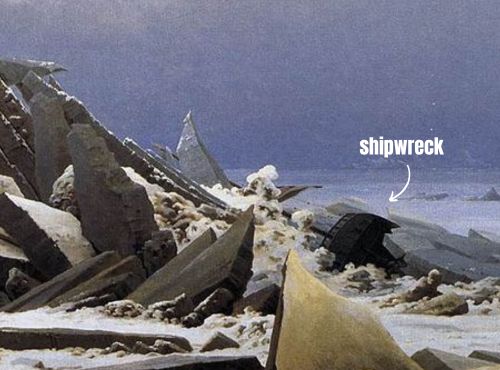

E. Caspar David Friedrich, The Sea of Ice (1823–24)

Friedrich’s painting captures the Romantic preoccupation with the sublime, where nature’s power overawes human ambition.

- Nature as Metaphor: The jagged, fractured ice and the wrecked ship symbolize destruction, despair, and the indifference of nature. The absence of human figures amplifies the painting’s existential message: the futility of human control in the face of nature’s overwhelming force.

- Romantic Sublimity: Beyond its dramatic presentation, The Sea of Ice is an allegory for human vulnerability. Friedrich’s use of light, texture, and perspective invites spiritual and existential contemplation, elevating the work from a depiction of nature to a meditation on life’s fragility.

- Interpretation Tip: Look beyond the immediate subject matter to uncover broader philosophical or emotional themes. Romantic landscapes often function as metaphors for inner states or universal truths.

These analyses demonstrate how symbols enrich an artwork’s narrative and emotional resonance. By delving into the details, viewers can uncover hidden layers of meaning, transforming their experience of art into a journey of discovery.

Section V: Practical Tips for Uncovering Symbols

Symbols in art offer a window into the minds of artists and the cultures they inhabit. However, interpreting them can sometimes feel daunting. Here are practical strategies to help unlock the hidden meanings of art while keeping the experience enjoyable and enriching.

1. Look for Recurring Motifs

Symbols often appear repeatedly within a single work or across an artist’s body of work. By identifying patterns or recurring objects, viewers can start to piece together their significance. For example:

- In Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights, the repeated presence of owls suggests themes of folly and moral blindness, prompting viewers to consider how these ideas relate to the painting’s fantastical narrative.

- In Pre-Raphaelite works, objects like mirrors, flowers, and water frequently symbolize themes of self-reflection, purity, and transformation.

Actionable Tip: Take note of motifs that seem out of place or unusually emphasized. They are often deliberate clues left by the artist.

2. Use Context Clues

Art does not exist in isolation. Understanding the historical, religious, or cultural backdrop can enrich interpretation. For instance:

- Northern European still-life paintings often include decaying fruit, skulls, or extinguished candles as symbols of mortality and the fleeting nature of life. Such symbols reflect the moral values and religious tensions of the Reformation.

- Eastern art, such as Hokusai’s The Great Wave off Kanagawa, often incorporates Buddhist concepts like impermanence and harmony with nature.

Actionable Tip: Research the time period, region, or personal circumstances of the artist. Museum guides and exhibition texts can offer invaluable insights.

3. Consult Resources

No one expects you to know every symbol at first glance! Utilize tools and resources to deepen your understanding:

- Museum Guides and Plaques: These often provide helpful explanations tailored to the specific artwork or exhibition.

- Books on Iconography: Titles like The Dictionary of Symbols by Jean Chevalier and Alain Gheerbrant are excellent references.

- Online Databases: Platforms such as Google Arts & Culture provide access to curated content and expert analyses.

Actionable Tip: Keep a list of symbols or references you find intriguing and explore them further through these resources.

4. When Symbols Remain Elusive

Sometimes, the meaning of an artwork resists interpretation. Rather than feeling frustrated, shift your focus to other aspects of the piece:

- Examine its composition, colours, or brushwork to appreciate its aesthetic and technical merits.

- Embrace the ambiguity and allow the artwork to evoke personal reflections or emotions.

Encouragement: Not every symbol needs to be decoded. Art is as much about the experience it evokes as it is about its meaning. Stay present, enjoy the process, and remember that appreciating art is a journey, not a test.

Applying these tips can deepen your connection with art, uncover hidden layers of meaning, and enrich your overall experience. In the final installment of this series, we’ll explore how to develop your own taste and style in art appreciation, taking your journey to the next level.

Conclusion

Symbols in art serve as keys to understanding the layers of meaning that artists embed in their work. They reveal not only the artist’s intent but also the societal norms, historical events, and universal human experiences that shaped their creation. Whether overtly displayed or subtly woven into the composition, symbols invite us to engage with art on a deeper level, turning visual experiences into opportunities for reflection, discovery, and dialogue.

Throughout this exploration of symbolism and iconography, we’ve seen how objects like flowers, animals, and religious imagery can transform the surface beauty of a painting into a profound narrative. From the rich allegories of Pieter Aertsen’s A Meat Stall to the evocative Romanticism of Friedrich’s The Sea of Ice, art demonstrates its capacity to speak to audiences across generations.

Symbols connect us to the past and inspire us to find personal meaning in the present. They challenge us to see beyond what meets the eye and to interpret the world through the artist’s lens. By delving into the language of art, we decode its messages and enrich our appreciation for the creativity and complexity of human expression.

In the next post, “From Realism to Abstraction: Navigating Different Art Styles,” we’ll explore how artists have pushed boundaries to redefine art’s purpose and form. Join us as we trace the evolution of styles and learn to appreciate art’s infinite possibilities.

What About You?

Have you ever encountered a piece of art that left you pondering its hidden meanings? Do you have a favourite symbolic artwork or an experience of discovering unexpected layers of meaning? Share your thoughts in the comments below. I’d love to hear your perspective!

Further Reading and Resources

Explore more about art appreciation and symbolism with these resources. Whether you want to deepen your understanding or start your journey, these suggestions will guide you.

Related Posts on Only Anton

- How to Get the Most Out of Your Museum Visit: Practical tips for making your museum experience enriching and memorable.

- Exploring Composition: The Foundation of Visual Art: Understand how artists structure their work to guide the viewer’s eye and create meaning.

- The Magic of Colour: Understanding Colour Theory in Art: Dive into how artists use colour to evoke emotions and shape narratives.

- The Artist’s Hand at Work: Brushwork and Techniques: Discover how brushwork reveals the artist’s intent and style.

External Resources

Let these resources inspire your journey into the rich and fascinating world of symbolism in art!

Books

- Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art by James Hall (2014): A comprehensive reference guide to the meanings and significance of symbols, themes, and subjects commonly found in Western art. Find it at your library, browse online, or grab your copy here.

- The Secret Language of the Renaissance: Decoding the Hidden Symbolism of Italian Art by Richard Stemp (2018): Explores the symbolic and allegorical meanings in Italian Renaissance art, revealing the cultural and philosophical context behind famous works. Check your local library, search online, or order a copy here.

- Symbols in Art by Matthew Wilson (2020): A visually engaging introduction to the use of symbols in art history, highlighting key motifs and their meanings across various periods and styles. Discover it at your library, look it up online, or purchase your copy here.

- Symbols and Allegories in Art by Matilde Battistini (2005): A richly illustrated exploration of allegorical and symbolic imagery in art, focusing on how artists across centuries have used these devices to convey complex ideas. Explore it at a nearby library, search the web, or buy it directly here.

- Saints in Art by Rosa Giorgi (2003): A guide to identifying saints and their attributes in religious art, providing insight into the iconography of Christian art traditions. See if your library has it, look online, or snag a copy here.

- Floriography: An Illustrated Guide to the Victorian Language of Flowers by Jessica Roux (2020): A beautifully illustrated book that decodes the symbolic meanings of flowers in Victorian culture, offering insights into how flowers communicate emotions and messages. Locate it at a library, check online options, or purchase it here.

- What Paintings Say: 100 Masterpieces in Detail by Rose-Marie Hagen and Rainer Hagen (2016): Analyzes 100 iconic works of art in detail, uncovering hidden meanings, historical context, and fascinating narratives behind each painting. Look it up at a local library, browse online, or buy your copy here.

- Great Paintings Explained by Christopher P. Jones (2022): Offers accessible explanations of significant works of art, revealing the stories, symbols, and techniques that make these masterpieces compelling. Find it at your library, browse online, or grab your copy here.

Practical Tools and Websites

- Museum guides and plaques: Many museums offer detailed guides or audio tours to explain symbolic meanings.

- Google Arts & Culture: A rich platform offering virtual tours, high-resolution images, and in-depth articles on art, history, and culture from museums and cultural institutions worldwide.

- Metropolitan Museum of Art: The official website of The Met, providing access to an extensive collection of art, detailed descriptions of works, and educational resources on a wide range of artistic and cultural topics.

Works Cited (in order of appearance)

Images used in this post are for educational and commentary purposes under Fair Use principles. Where possible, sources are credited, and permissions are obtained for licensed materials.

- Pieter Bruegel, Netherlandish Proverbs, 1559. Oil on panel. Gemäldegalerie, Berlin.

- Andrea Mantegna, Saint Sebastian, 1456–1459. Oil on panel. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

- Jan van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait, 1434. Oil on panel. National Gallery, London.

- Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, 1490–1510. Oil on panel. Museo del Prado, Madrid

- Winslow Homer, The Gulf Stream, 1899. Oil on canvas. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

- Jacques-Louis David, The Death of Marat, 1793. Oil on canvas. Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels.

- Stephan Lochner, Madonna of the Rose Bower or Virgin in the Rose Bower, 1440–1442. Oil on panel. Wallraf-Richartz Museum, Cologne.

- Simone Martini and Lippo Memmi, Annunciation with Saint Margaret and Saint Ansanus, 1333. Tempera and gold on panel. Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

- Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Procession to Calvary, 1564. Oil on panel. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

- Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Adoration of the Magi in the Snow, 1563. Oil on panel. Am Römerholz, Winterthur.

- Katsushika Hokusai, The Great Wave off Kanagawa, 1831. Ukiyo-e woodblock print. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

- Willem Claeszoon Heda, Still Life with a Gilt Cup, 1635. Oil on canvas. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

- Unknown artist, Portrait of a Woman of the Hofer Family, 1470. Oil on panel. National Gallery, London.

- Frida Kahlo, The Two Fridas, 1939. Oil on canvas. Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City.

- Théodore Géricault, The Raft of the Medusa, 1818-1819. Oil on canvas, Louvre, Paris.

- Salvador Dalí, The Persistence of Memory, 1931. Oil on canvas. Museum of Modern Art, New York.

- Yang Yongliang, View of Tide, 2008. Inkjet print of a composite photograph. M+ Sigg Collection, Hong Kong.

- Pieter Aertsen, A Meat Stall with the Holy Family Giving Alms, 1551. Oil on panel. North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, North Carolina.

- Hans Holbein the Younger, The Ambassadors, 1533. Oil on panel. National Gallery, London.

- Gustave Moreau, Oedipus and the Sphinx, 1864. Oil on canvas. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

- John William Waterhouse, The Lady of Shalott, 1888. Oil on canvas. Tate Britain, London.

- Caspar David Friedrich, The Sea of Ice, 1823–1824. Oil on canvas. Kunsthalle Hamburg.