Introduction

Ancient noodles, dating back some 4,000 years, have been discovered along the banks of the Yellow River in Qinghai. The discovery of the world’s oldest noodles heralds just one of the many contributions made by China’s Eight Great Traditions to culinary history. China is home not only to one of the world’s earliest civilizations. It is also the birthplace of foods that have become global staples. Beyond noodles, ancient China pioneered ice cream during the Tang dynasty. China was also the first to ferment soybeans into the paste that later inspired Japanese miso. Such innovations underscore the rich heritage of Chinese cuisine, a tradition that has evolved and influenced culinary practices worldwide.

At the heart of Chinese culinary culture lie the Eight Great Traditions: Chuan, Lu, Yue, Huaiyang, Hui, Min, Xiang, and Zhe. Each tradition is a pillar of regional diversity with distinct flavours, techniques, and local ingredients. While unique in their characteristics, these regional cuisines share a guiding philosophy of balance and harmony that creates a dynamic yet unified culinary and cultural heritage.

This post, the first in a series exploring the Eight Great Traditions, will set the stage by offering a historical backdrop, tracing the evolution from the Four Great Traditions recognized during the Qing dynasty to the expanded list of eight. Join me as we embark on a flavourful journey through China’s regional culinary heritage. We will preview each tradition’s unique offerings and discover how these regional cuisines continue to shape Chinese food culture today.

Section I: Historical Context of the Eight Great Traditions

The Four Great Traditions

The Eight Great Traditions of Chinese cuisine reflect centuries of cultural and culinary evolution, rooted in distinct regional flavours and ingredients. Originally, Chinese cuisine was categorized into the Four Great Traditions: Chuan, Lu, Yue, and Huaiyang. During the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912 CE), these four cuisines each represented a major region of China—Chuan (Sichuan) in the West, Lu (Shandong) in the North, Yue (Cantonese) in the South, and Huaiyang (Jiangsu) in the East. With their refined techniques and unique regional ingredients, these Four Great Traditions were considered the pinnacle of Chinese culinary arts. Each one embodies the local tastes and styles honed over generations.

The Expanded Eight Traditions

In more recent times, however, modern recognition of China’s culinary diversity has expanded this original list. The modern Eight Great Traditions now include four additional cuisines: Hui (Anhui), Min (Fujian), Xiang (Hunan), and Zhe (Zhejiang). This broader categorization reflects a deeper appreciation for the regional variations that make up China’s culinary landscape. A key milestone in formalizing this expanded list came in 1980. Wang Shaoquan, a journalist for People’s Daily, published an article acknowledging these additional cuisines as unique and influential within Chinese culinary tradition.

An Alternate Schema

A common Chinese saying captures these regional distinctions in a simple phrase:

东甜 南咸 西酸 北辣 (dong tian, nan xian, xi suan, bei la)

This phrase translates to “The East is sweet, the South is salty, the West is sour, and the North is hot.” While this expression captures general regional preferences, it’s an oversimplification. For instance, although sour flavours are prominent in the West, that region is also famous for its spicy food, especially in Sichuan. An alternative schema, the Original Four Schools, categorized many of the various regional cuisines under the broader traditions of Lu, (Huai)Yang, Yue, and Chuan. Both approaches offer a fascinating framework for understanding China’s culinary heritage, highlighting the diversity within overarching categories.

Section II: Culinary Innovations and Global Influence

While Chinese cuisine has evolved within its own borders, it has also profoundly impacted global culinary traditions. With a rich history of food innovations, China has been credited with inventions that have shaped dining worldwide. Noodles, likely the oldest ever discovered, were unearthed near the Yellow River. The Tang dynasty (618–907 CE) developed a form of ice cream using dairy—a precursor to the frozen treats enjoyed today. Other iconic innovations include early forms of miso and even ketchup, which originated as a fermented fish sauce called “ke-tsiap.”

The cultural reach of Chinese cuisine extends well beyond its borders. Chinese food culture has become a beloved part of communities worldwide. Chinese regional specialties have influenced culinary practices in Southeast Asia, North America, and beyond. This remarkable influence underscores the uniqueness and adaptability of China’s regional cuisines, setting the stage for exploring the Eight Great Traditions.

Section III: Overview of the Eight Great Traditions of Chinese Cuisine

China’s Eight Great Traditions are celebrated as the foundation of its diverse culinary culture. Each brings a unique set of flavours, techniques, and local ingredients. Spanning every region of China, these traditions offer a remarkable variety that reflects the country’s geographical, historical, and cultural diversity.

Chuan (Sichuan)

Renowned for its bold, spicy flavours, Chuan cuisine is perhaps best known for the ma la (麻辣) sensation, a tingling, numbing heat created by the Sichuan peppercorn. Dishes like hot pot, mapo tofu and kung pao chicken showcase this distinctive flavour profile that pairs the numbing spice with layers of rich, deep heat. Beyond the spice, Chuan cuisine makes creative use of garlic, ginger, and fermented sauces, creating robust, aromatic, and complex flavours.

Lu (Shandong)

Hailing from China’s northeastern coast, Lu cuisine emphasizes fresh, bold flavours with a focus on seafood. Due to the region’s coastal geography, fish, shrimp, and sea cucumber play central roles in many dishes. Techniques like braising and quick frying preserve the natural flavours of ingredients. Meanwhile, dishes like braised abalone and sweet and sour carp highlight Shandong’s sophisticated approach to seafood. Lu cuisine is one of the oldest and most revered traditions, with hearty flavours and an emphasis on umami that has influenced imperial kitchens for centuries.

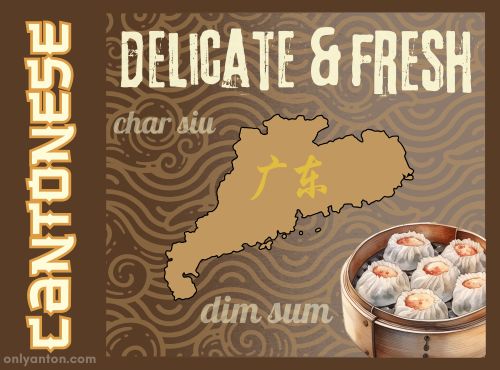

Yue (Cantonese)

Perhaps the most globally recognized Chinese cuisine is Yue (or Cantonese). Yue cuisine highlights delicate flavours and puts emphasis on fresh, high-quality ingredients. This tradition celebrates the natural taste of ingredients, often through steaming, stir-frying, and roasting techniques. Roast meats, particularly char siu (barbecue pork) and roast duck, are beloved staples. Meanwhile, dim sum culture brings a social dining experience to the table with various small, artfully crafted dishes. The simplicity of Yue cuisine belies the skill required to perfect its delicate flavours.

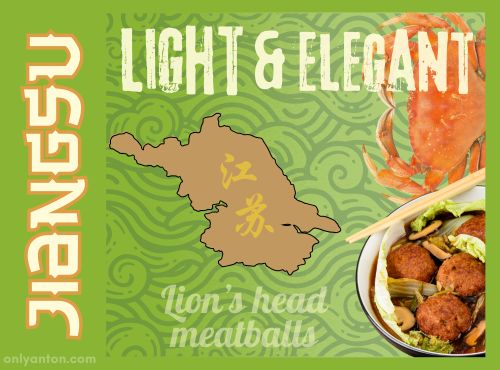

Huaiyang (Jiangsu)

Huaiyang cuisine originates from the eastern Jiangsu region. Characteristics of this food tradition include elegant presentation, precise knife skills, and a focus on texture. Seasonal ingredients are central, with a lighter approach to seasoning that lets the quality of produce shine. Famous Huaiyang dishes include crystal-clear crab meat soup and “lion’s head” meatballs. It is a cuisine with a refined, almost delicate aesthetic, often emphasizing the natural sweetness of vegetables and the subtle flavour of freshwater fish.

Hui (Anhui)

Drawing from the mountainous Anhui region, Hui cuisine is full of rustic and hearty flavours. It often incorporates wild herbs, mushrooms, and other ingredients from local mountains and rivers. Braising and stewing are standard techniques that bring out the richness of flavours. Dishes like bamboo shoots with dried chillies and braised soft-shell turtle highlight simple ingredients in nourishing, earthy dishes. Authenticity and a respect for nature’s bounty are hallmarks of Hui cuisine.

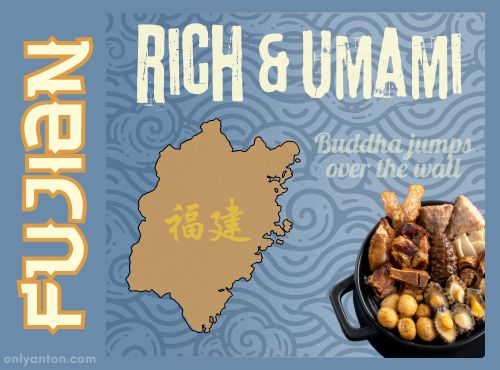

Min (Fujian)

Min cuisine from Fujian Province is famous for its umami-rich dishes that often feature seafood and soups. The cuisine makes ample use of light, flavourful broths and red yeast rice, which imparts a unique flavour and colour to dishes. Known for its refined soups, such as Buddha Jumps Over the Wall, Fujian cuisine also emphasizes balance and lightness, with dishes that have a refreshing, savoury depth. Min cuisine is a study in subtlety, bringing out layers of flavour through delicate seasonings and careful preparation.

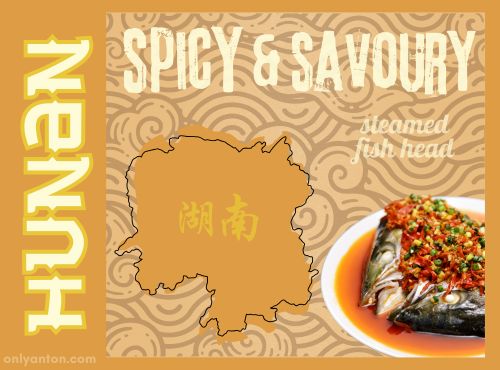

Xiang (Hunan)

Known for its fiery and savoury flavours, Xiang cuisine from Hunan province is bold and unafraid of packing a punch with chillies. Unlike Sichuan, however, Hunan’s spice is purely hot, without the numbing sensation of peppercorns. Dishes like spicy steamed fish heads and stir-fried pork with green peppers showcase the freshness of ingredients and the distinctive heat that defines Xiang cuisine. The flavours are intense and vivid, and the cuisine has a reputation for being one of China’s spiciest.

Zhe (Zhejiang)

Zhe cuisine, originating from the southeastern Zhejiang province, focuses on light, fresh flavours that highlight the natural taste of ingredients. Known for dishes that use seafood, bamboo shoots, and seasonal produce, Zhe cuisine aims to be refreshing and subtly seasoned. Techniques like quick stir-frying and light steaming are standard in dishes like West Lake vinegar fish and Dongpo pork. People refer to Zhejiang as the “land of fish and rice” due to its cuisine, which features these ingredients with gentle flavours and elegant simplicity.

Each of these Eight Great Traditions offers a unique window into China’s diverse culinary heritage. Together, they create a rich panoply of flavours, techniques, and regional identities that continue to evolve and inspire.

Section IV: Culinary Philosophy of Balance and Harmony

Chinese cuisine is deeply rooted in a philosophy of balance and harmony. Flavours, textures, and presentations are carefully orchestrated to create a holistic dining experience. This philosophy goes beyond taste to encompass health, visual appeal, and even cultural values.

Flavour Balance

A key element in Chinese culinary philosophy is a balance of five essential flavours: sour, sweet, bitter, spicy, and salty. These flavours are not just combined randomly. Instead, they are skillfully balanced to complement each other, creating complex and satisfying dishes. In some traditions, this concept expands to the Eight Great Tastes, adding dimensions like pungency and freshness, as my post on Chinese flavour profiles has discussed. This thoughtful blending of flavours reflects a broader Chinese cultural appreciation for harmony in all things, where extremes are tempered by moderation.

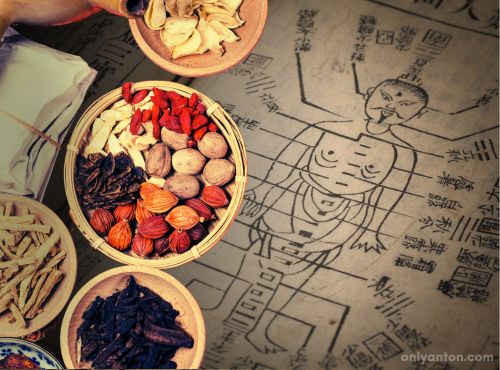

Influence of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM)

Chinese cuisine also reflects the influence of Traditional Chinese Medicine, which emphasizes balance as a foundation for health and well-being. In TCM, ingredients are classified by their energetic properties—cooling or warming, for example. These medicinal principles create dishes that nourish the body according to seasonal needs or personal health. Such an approach adds another layer of meaning to Chinese food. Each meal is seen as nourishment and a means of maintaining harmony within the body.

Cultural Values in Presentation

The concept of harmony extends to the presentation, texture, and colour of dishes. Chinese chefs carefully consider visual appeal, arranging food to create a balanced, inviting plate. Colours are chosen to be vibrant yet harmonious. Textures are layered to create a satisfying mouthfeel. This focus on presentation highlights the importance of beauty and harmony. Chefs design dishes to appeal to all the senses and enrich the dining experience in ways beyond taste alone. In Chinese culture, food celebrates artistry and balance, reflecting values that resonate deeply across all aspects of life.

Section V: The Modern Influence of the Eight Great Traditions

The Eight Great Traditions of Chinese Cuisine have shaped more than the regional dining patterns within China. They have become a vital part of the global culinary landscape. Chinese communities around the world celebrate these traditions. From North America to Southeast Asia and Europe, Chinese restaurants showcase the flavours, techniques, and philosophies that make each tradition unique.

Global Reach

Dishes from the Eight Great Traditions have become staples in international cities, often sparking enthusiasm among locals and visitors alike. Cantonese dim sum houses are widespread in places like San Francisco and London. Sichuan hotpot restaurants have made their way to cities across Europe and North America, introducing diners to the numbing spice of Sichuan peppercorns.

Beyond traditional dishes, Chinese cuisine has also evolved into new forms in regions where Chinese communities have settled. In Southeast Asia, countries like Malaysia and Singapore feature vibrant culinary scenes where Cantonese and Hokkien influences combine with local spices and ingredients. North America has also seen the emergence of iconic Chinese-American dishes like Chop Suey and General Tso’s Chicken. While not traditional, these creations are inspired by the flavours and techniques of the Eight Great Traditions. Variations such as these reflect the adaptability of Chinese cuisine and its ability to resonate with diverse palates worldwide.

Culinary Innovation

Modern chefs are reimagining these culinary traditions, blending time-honoured techniques with global influences. For instance, chefs might incorporate new ingredients or create fusion dishes that retain the essence of traditional flavours while appealing to contemporary tastes. This creativity is evident in fusion cuisines that have emerged around the world.

At Patois in Toronto, a fusion of Chinese and Jamaican cuisine offers dishes like jerk chicken chow mein and Jamaican patties served alongside Chinese “pineapple” buns. Flor de Mayo in New York City combines Chinese and Cuban influences, serving Spanish-style dishes alongside Cantonese specialties. In Fall River, Massachusetts, Mee Sum Restaurant is home to the unique Chow Mein Sandwich. The sandwich features crispy noodles in brown gravy served in a hamburger bun—a true reflection of regional culinary adaptation. In some high-end restaurants, chefs employ molecular gastronomy techniques, presenting traditional dishes like “deconstructed” Peking duck or hotpot broths infused with non-traditional herbs in innovative formats.

Continued Relevance

Despite these modern twists, the Eight Great Traditions remain a fundamental part of Chinese cooking, symbolizing Chinese cuisine’s rich heritage and adaptability. They continue to inspire both traditional cooks and modern chefs. Chinese food is a dynamic, evolving part of the global culinary scene, revered for its ability to balance innovation with respect for tradition.

Conclusion

The Eight Great Traditions of Chinese Cuisine are pillars of China’s rich culinary heritage. Each tradition reflects its region’s unique geography, climate, and cultural influences. Together, they represent the core of Chinese culinary philosophy, a blend of balance, harmony, and health that has shaped Chinese food for centuries. From the bold spices of Sichuan to the refined techniques of Huaiyang, these traditions capture the incredible diversity and depth of Chinese cuisine, offering endless avenues for culinary exploration.

In this series, we’ll explore each of these eight traditions, uncovering the unique flavours, cooking methods, and dishes that define them. Our next post will explore Chuan, or Sichuan, cuisine—a vibrant, spicy tradition known for its distinctive ma la (numbing heat) flavours. Join me as I journey through each region, bringing the best of Chinese food culture to life.

What About You?

Have you tried dishes from any of the Eight Great Traditions? What’s your favourite regional Chinese cuisine, or is there a dish you’d love to learn more about? Share your experiences with Chinese food, whether at home or abroad, in the comments below! I’d love to hear your stories and your recommendations.

Further Reading and Resources

Related Posts on Only Anton

- The Eight Great Tastes of Chinese Cuisine: A look at the primary flavours that underpin the Eight Great Traditions.

- Sichuan Cuisine: A Culinary Odyssey in Chengdu: Dive into the flavours and techniques that make Sichuan food so distinctive.

- Cha Chaan Teng: Hong Kong’s Diner Food: Discover the iconic dishes of Hong Kong’s unique café culture.

- MSG in Asian Food: Dispelling Myths and Embracing Umami: Explore the role of MSG in enhancing umami flavours across Asian cuisines.

- The Food of Tibet: Lhasa’s Unique Cuisine: Uncover the distinctive ingredients and dishes of Tibetan cuisine.

External Resources

These resources are perfect for readers who want to deepen their knowledge of Chinese culinary traditions, history, and techniques.

Books

- All Under Heaven: Recipes from the 35 Cuisines of China by Carolyn Phillips: This comprehensive guide provides recipes and cultural insights into the diverse culinary traditions of China, making it an ideal resource for anyone interested in regional Chinese cooking. Check your local library, search online, or order a copy right here.

- Land of Fish and Rice: Recipes from the Culinary Heart of China by Fuchsia Dunlop: A deep dive into Jiangnan cuisine, specifically Zhejiang and Jiangsu provinces, two regions contributing to the Eight Great Traditions. Pick it up at a library, browse for it online, or buy a copy through this link.

- Sharks’ Fin and Sichuan Pepper: A Sweet-Sour Memoir of Eating in China by Fuchsia Dunlop: This engaging memoir captures Fuchsia Dunlop’s culinary journey through China, with insights into Sichuan cuisine and beyond. Borrow from a library, find it online, or get it here if you’d like your own.

Articles

- “Chinese Medicinal Cuisine/Food Therapy,” China Highlights: Explores the principles of Chinese food therapy, emphasizing the role of diet in Traditional Chinese Medicine for balancing health and energy. Read the article here.

- “Explore Chinese Food Culture: A Deep Dive into Tradition” by Nhu Le, Ni Hao Ma Mandarin Learning Lab: Offers an in-depth look at Chinese food culture, its historical evolution, and the traditions that shape modern Chinese cuisine. Find the article here.

- “Food in Chinese Culture” by K. C. Chang, Asia Society: Discusses the cultural significance of food in Chinese society, highlighting its role in rituals, symbolism, and social practices. Read the article here.

YouTube Channel

- Chinese Cooking Demystified: This channel provides accessible, authentic recipes and techniques for Chinese cooking, focusing on foundational skills and traditional methods relevant to all Eight Great Traditions.

Websites

- Taste Atlas: Chinese Cuisine: This website offers an overview of key regional dishes and ingredients, along with cultural context that complements each of the Eight Great Traditions.

- “Chinese Cuisine,” Wikipedia: Provides a comprehensive overview of Chinese cuisine, including its history, regional variations, ingredients, and preparation methods.