Introduction: Klimt and the Allure of Vienna

Few artists have left a more dazzling imprint on the art world than Gustav Klimt, the Austrian master whose gold-laden canvases continue to captivate audiences. His work symbolizes Vienna’s artistic golden age, and nowhere is this more apparent than at the Upper Belvedere, home to his most famous masterpiece, The Kiss.

A Personal Encounter with The Kiss

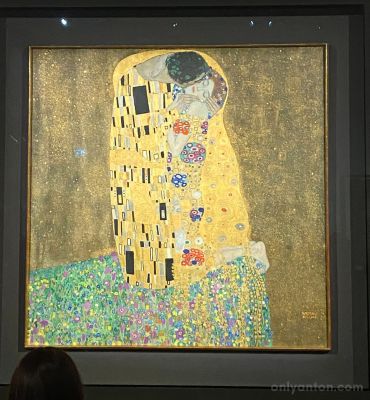

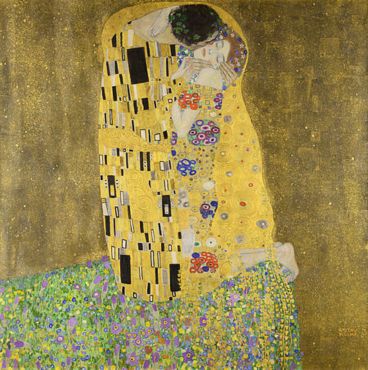

Standing before The Kiss at Vienna’s Upper Belvedere took me by surprise. I had seen this painting countless times—in books, on postcards, even as prints on tote bags—but nothing quite prepared me for its scale and presence in person. Larger than I expected (180 x 180 cm), the work radiates a golden glow that seems almost three-dimensional, its ornamented patterns shimmering under the gallery lights.

I visited in the late afternoon when the crowds had begun to thin, but there was still a steady flow of visitors gathering around Klimt’s most iconic painting. I waited patiently, letting the waves of people come and go until I finally had an unobstructed view. Taking it all in squarely, I marvelled at the intricate details—the mosaic-like robes, the delicate rendering of hands and faces, and the textured embellishments that give the painting a sense of tactility rarely captured in reproductions. Stepping closer, I could appreciate how Klimt’s gilded forms seem to emerge from the canvas, blending sensuality and spirituality in a way few artists have ever achieved.

Klimt and the Soul of Vienna

Gustav Klimt (1862-1918) was more than just a painter; he was a revolutionary figure who helped shape Vienna’s identity as a cultural capital. As the co-founder of the Vienna Secession in 1897, Klimt and his contemporaries sought to break free from rigid academic traditions, embracing modernity with the famous motto: “To each age its art, to art its freedom.”

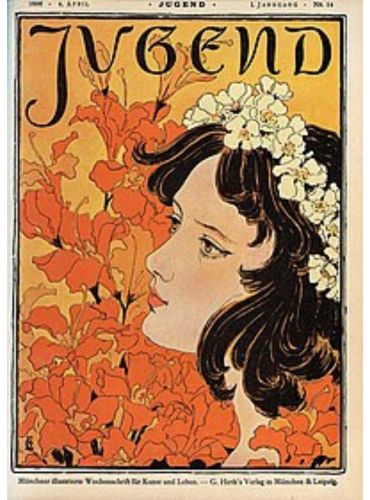

His work became synonymous with Jugendstil, the Austrian counterpart to Art Nouveau, which infused fine and decorative arts with intricate ornamentation, flowing lines, and bold symbolism. Just as Paris had its Belle Époque, Vienna’s fin-de-siècle period was a time of artistic and intellectual ferment, with Klimt at its centre. His art reflected the city’s duality—rational yet decadent, restrained yet indulgent—mirroring the era’s fascination with progress and sensuality.

Why Klimt Still Captivates Today

Klimt’s paintings remain as mesmerizing today as they were over a century ago. His work blends mystery, eroticism, and allegory, creating images that are both intimate and universal. His signature gold-drenched style, inspired by Byzantine mosaics and Japanese prints, has become one of the most recognizable in art history. Yet beyond the gilded surfaces lie deeper themes—love, death, renewal, and transcendence—imbued with rich symbolism and emotional depth.

His legacy extends beyond museums. His influence permeates fashion, design, and popular culture, ensuring that Klimt’s vision continues to shine long after his time.

What to Expect in This Guide

In this post, we will explore Klimt’s life, artistic evolution, and masterpieces, focusing particularly on:

- His early career and the Vienna Secession,

- His most famous works, including The Kiss, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, and Judith with the Head of Holofernes,

- Where to see Klimt’s paintings today, from Vienna’s Belvedere Palace to the Neue Galerie in New York,

- His enduring influence on modern art and design.

Whether you are a seasoned art enthusiast or a traveller planning to see Klimt’s work in person, this guide will offer insights into his genius and where to experience it firsthand.

Klimt’s Biography & Artistic Context

Klimt’s Early Life and Training

Gustav Klimt was born in 1862 in Baumgarten, then a suburb of Vienna, into a modest yet artistically inclined family. His father, Ernst Klimt, was a gold engraver, a profession that may have influenced Gustav’s later fascination with ornamentation and gilded surfaces. Despite financial hardships, the Klimt family encouraged artistic pursuits, and Gustav’s talent became evident early on.

At age 14, Klimt enrolled in the Vienna School of Arts and Crafts (Kunstgewerbeschule), a prestigious institution dedicated to training young artists in decorative and applied arts. Unlike the Academy of Fine Arts, which adhered strictly to classical techniques, the Kunstgewerbeschule emphasized practical craftsmanship and ornamental design, preparing students for careers in architecture, interior decoration, and mural painting.

Klimt excelled in academic-style painting, a highly detailed and polished approach that adhered to traditional principles of realism, perspective, and classical composition. Early in his career, he worked alongside his brother Ernst and fellow artist Franz Matsch, forming the Künstler-Compagnie (Company of Artists). This trio specialized in ceiling frescoes, theatrical stage sets, and large-scale public commissions, earning acclaim for their meticulously executed murals.

Notable commissions included ceiling decorations for Vienna’s Burgtheater (1886–1888) and the grand staircase at the Kunsthistorisches Museum (1890–1891). These projects established Klimt as a respected academic painter—but he soon sought to break free from rigid artistic conventions.

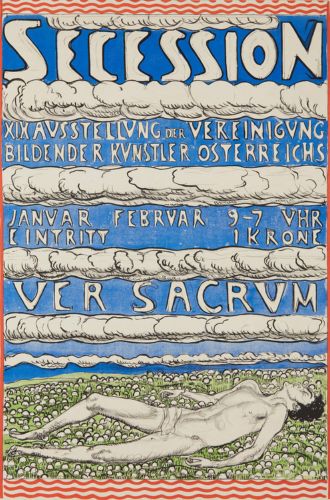

The Vienna Secession: Breaking Away from Tradition

By the late 19th century, Vienna’s cultural landscape had dramatically changed. A younger generation of artists, architects, and intellectuals sought to challenge the conservative dominance of the Vienna Academy, which dictated artistic taste and upheld strict academic traditions. Frustrated by these constraints, Klimt emerged as a leading figure in this movement.

In 1897, Klimt co-founded the Vienna Secession, a radical group of artists committed to artistic innovation and freedom. Their motto, emblazoned on the Secession Building, declared:

“To each age its art, to art its freedom.”

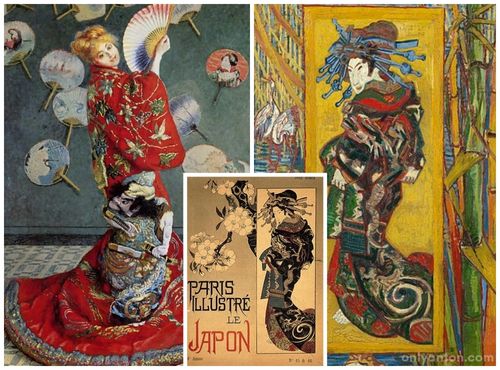

The Secessionists rejected historical revivalism, favouring instead modern, decorative, and symbolist aesthetics influenced by Japanese prints, Art Nouveau (Jugendstil), and contemporary European movements. They launched Ver Sacrum (“Sacred Spring”), an avant-garde magazine that served as a platform for their artistic philosophy, featuring experimental designs and essays on emerging artistic trends.

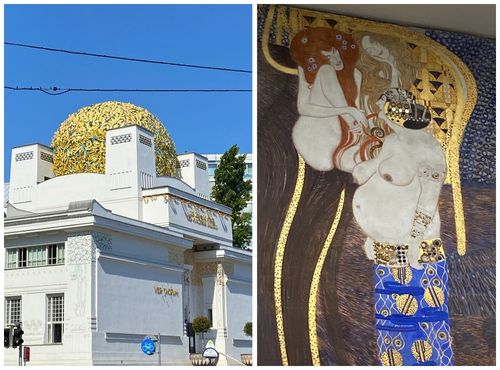

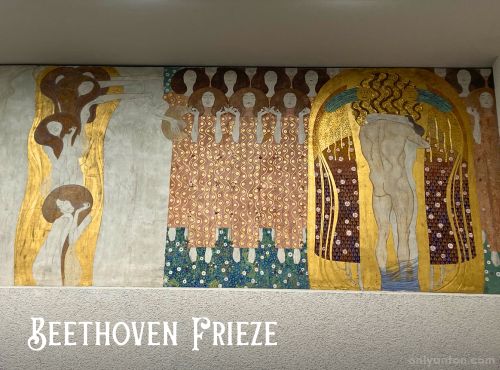

The movement’s most striking physical representation was the Secession Building, designed by architect Joseph Maria Olbrich in 1898. Its gleaming golden dome, composed of 3,000 gilded laurel leaves, became a symbol of artistic rebellion and modernity. Inside, the building housed groundbreaking exhibitions, including Klimt’s monumental Beethoven Frieze (1902)—a swirling, ethereal mural celebrating art as a form of spiritual transcendence.

Although the Vienna Secession championed artistic liberty, it also provoked a conservative backlash, particularly when Klimt’s increasingly bold and sensuous style came to the forefront.

Scandal & Controversy: Public Backlash Against Klimt

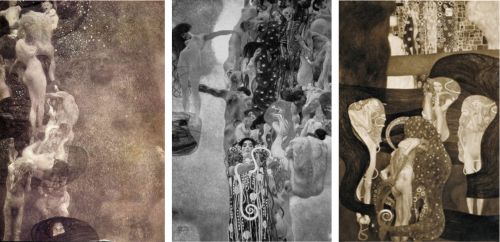

One of the most defining moments of Klimt’s career—and the event that pushed him toward complete artistic independence—was the controversy surrounding his Faculty Paintings, commissioned for the University of Vienna’s Great Hall.

Klimt’s task was to create three allegorical works: Philosophy, Medicine, and Jurisprudence. Instead of adhering to traditional academic expectations, Klimt produced bold, erotic, and symbolist compositions filled with nude figures, swirling dreamscapes, and ambiguous meanings. The paintings shocked the conservative elite, who deemed them pornographic and inappropriate for a university setting.

Public outrage was fierce, and the government withdrew the commission. Klimt refused to compromise his vision and alter the paintings. He returned the payment and kept the works for himself—an unprecedented act of defiance.

This rejection marked a turning point in Klimt’s career. Liberated from institutional control, he fully embraced his artistic path, transitioning into his most famous period: The Golden Phase. Gilded surfaces, mosaic-like ornamentation, and ethereal compositions characterized this dazzling era of opulence, sensuality, and artistic freedom.

Although the Faculty Paintings were tragically destroyed in World War II, Klimt’s response to the controversy set the stage for some of his most celebrated masterpieces. Klimt died in Vienna on February 6, 1918. He was buried at Hietzinger Cemetery in Hietzing, Vienna.

Klimt’s Masterpieces & Artistic Contributions

The Golden Phase & Decorative Brilliance

Gustav Klimt’s Golden Phase, spanning from the late 1890s through the early 1910s, marked the pinnacle of his artistic experimentation. During this time, he developed his most recognizable and opulent style, characterized by lavish gold leaf, intricate patterning, and a fusion of abstraction and realism. Inspired by various sources, Klimt’s work in this period transcended traditional painting and became a visual symphony of sensuality, symbolism, and ornamentation.

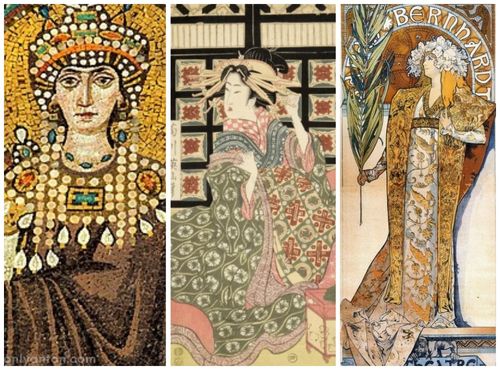

One of the most significant influences on Klimt’s Golden Phase was Byzantine mosaics, which he encountered during a trip to Ravenna, Italy, in 1903. The glimmering tesserae of San Vitale’s mosaics, with their shimmering gold backgrounds and stylized figures, profoundly shaped his approach to texture, light, and decoration.

Additionally, Klimt was deeply inspired by Japonisme, the European fascination with Japanese art that flourished in the late 19th century. Following Japan’s reopening to the West in the 1850s, Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints became widely available, influencing European artists such as Monet, Van Gogh, and Klimt. These prints emphasized flattened perspectives, bold outlines, and intricate patterns, which Klimt incorporated into his compositions.

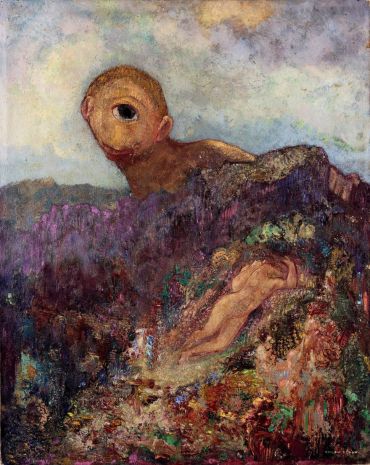

Another key influence was Symbolism, a late 19th-century movement that sought to express psychological depth, spirituality, and mythological themes rather than objective reality. Symbolist painters and writers like Odilon Redon and Gustave Moreau used dreamlike imagery, allegory, and decorative abstraction—elements that Klimt would adopt in his most famous works.

By fusing these inspirations, Klimt created highly ornamental compositions that blurred the boundaries between fine art and decorative arts. His use of gold leaf and mosaic-like patterns, combined with sensuous and often erotic imagery, set him apart as a visionary artist who pushed the limits of painting beyond conventional representation.

Featured Works of Gustav Klimt

1. The Kiss (1907–1908)

Arguably one of the most famous paintings in the world, The Kiss is the quintessential Klimt masterpiece. This gilded canvas, measuring 180 x 180 cm, depicts an embracing couple enveloped in a luminous, patterned cloak. Their faces and hands are rendered with breathtaking realism, while their bodies dissolve into a shimmering tapestry of gold and geometric forms.

Symbolism & Meaning:

- The Kiss is widely interpreted as a celebration of love, intimacy, and artistic transcendence.

- The golden background, reminiscent of Byzantine mosaics, creates a sense of timelessness and divine connection.

- The contrast between angular, masculine patterns on the man’s robe and circular, organic shapes on the woman’s garment represents the fusion of opposites—strength and softness, passion and serenity.

Composition & Emotional Depth:

- The couple is placed within a golden void, suggesting an otherworldly, dreamlike realm.

- Their clasped hands and closed eyes evoke complete emotional surrender.

- Positioning the figures at the edge of a flower-strewn precipice adds an element of delicate tension—suggesting both safety and the risk of falling.

Housed in Vienna’s Belvedere Palace, The Kiss remains the crown jewel of Austrian art, drawing thousands of visitors annually.

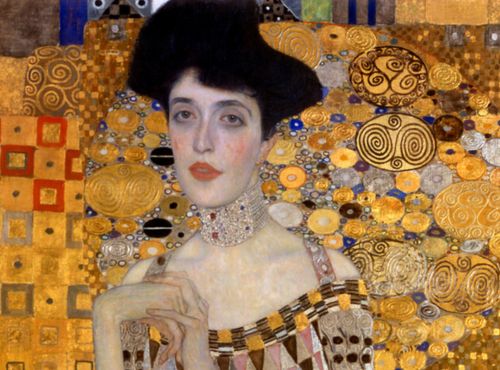

2. Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907) – “The Woman in Gold”

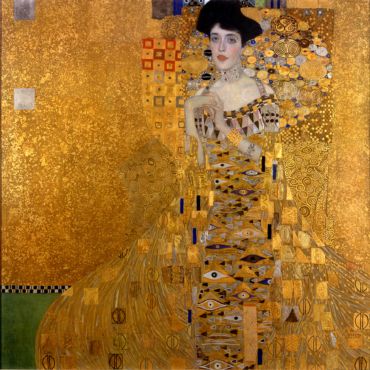

Known as “The Woman in Gold,” the Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I is one of Klimt’s most striking and luxurious works, encapsulating his Golden Phase at its most opulent. Commissioned by Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer, a wealthy Jewish industrialist, the portrait immortalizes his wife, Adele, as a patron of the arts and an emblem of elegance, power, and mystery.

Symbolism & Artistic Interpretation

- Adele’s elongated form and hypnotic gaze create a commanding yet enigmatic presence, exuding sensuality and self-assurance.

- The elaborate gold patterns surrounding her recall Byzantine mosaics, reinforcing an aura of timeless grandeur.

- Her delicate hands—one resting lightly on the other—lend an air of refinement and vulnerability, subtly contrasting with the geometric opulence of her surroundings.

- The integration of Egyptian, Mycenaean, and Japanese motifs reflects Klimt’s eclectic inspirations, merging influences into a uniquely Viennese style.

Composition & Visual Impact

- The painting’s ornate surface dissolves the boundary between figure and background, immersing Adele in a gilded world where decorative abstraction and realism intertwine.

- Unlike The Kiss, where figures are wrapped in a shared embrace, Adele emerges from the composition, her face and arms rendered with lifelike softness against the intricate gold-leaf patterns.

- Klimt employs a mosaic-like fragmentation, suggesting a fusion of portraiture and ornamental design—a hallmark of his Golden Phase.

- The floating, almost weightless quality of Adele’s presence lends the painting a dreamlike, iconic quality, making it one of the most recognizable and mesmerizing portraits in art history.

Today, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I is housed at the Neue Galerie in New York, where it remains a testament to Klimt’s mastery of portraiture and ornamental abstraction.

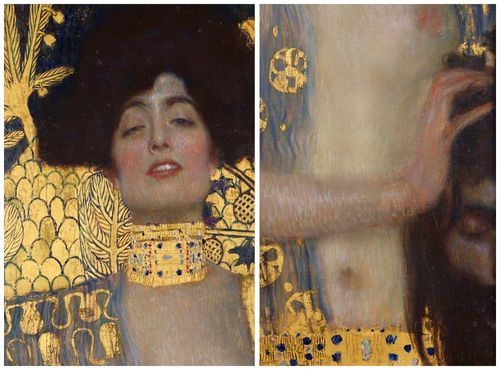

3. Judith with the Head of Holofernes (1901)

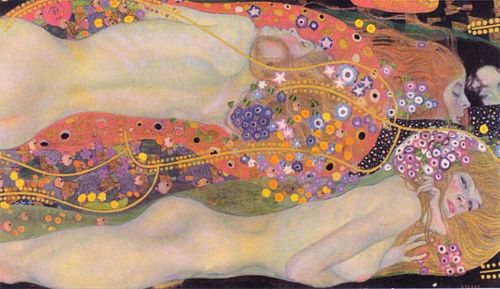

While The Kiss and Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I exude romance and opulence, Judith with the Head of Holofernes is Klimt at his most provocative. This darkly sensual reinterpretation of the biblical heroine transforms Judith from a triumphant warrior into a seductive femme fatale.

Eroticism and Violence:

- Unlike traditional portrayals of Judith as a devout saviour, Klimt presents her as a languid, self-assured beauty, her half-open lips and heavy-lidded gaze oozing seduction.

- The severed head of Holofernes, barely visible at the bottom, is secondary to Judith herself—shifting the painting’s focus from heroism to temptation.

Symbolism and Artistic Style:

- Swirling gold patterns and jewel-like ornamentation create an ethereal, dreamlike quality.

- The piece reflects Symbolist themes of female power and danger, aligning Judith with Klimt’s other enigmatic women, such as his later Danaë.

Judith with the Head of Holofernes may be found in Vienna’s Belvedere Palace, where it continues to mesmerize and provoke discussion.

Klimt’s Later Years & Landscapes

As Klimt moved beyond his Golden Phase, his work became brighter, looser, and more nature-focused.

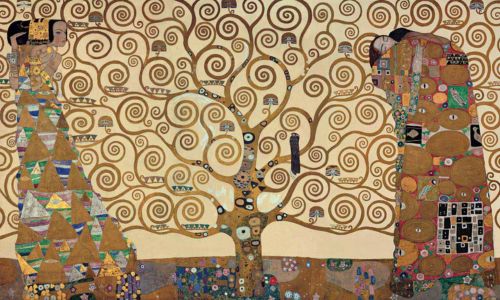

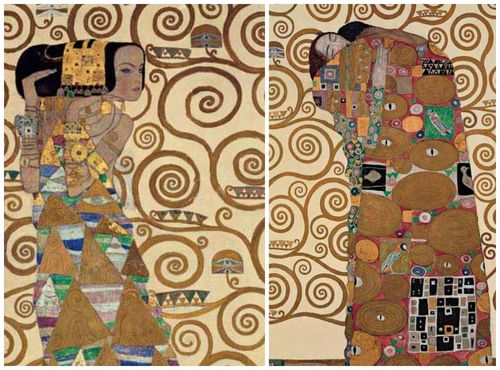

One of the most famous paintings from this later period is The Tree of Life (1909). Unlike his previous portraits, this piece is a symbolic and decorative composition featuring spiralling branches, golden hues, and intricate detailing. The tree represents renewal, growth, and the interconnectedness of all things.

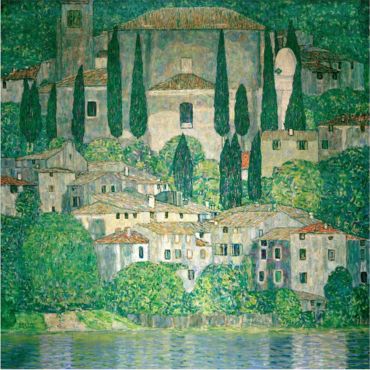

Klimt also turned his attention to landscapes and architectural scenes, producing works that contrast his earlier golden portraits:

- Flowering gardens, lakeside cottages, and woodland paths are painted in vivid greens, yellows, and blues.

- These compositions exhibit a playful, mosaic-like quality, showing a softer, more intimate side of Klimt’s artistic vision.

While often overlooked, his landscapes are testaments to his versatility, proving that Klimt was constantly evolving and not confined to a single style.

Where to See Klimt’s Work Today

Discovering Klimt’s Masterpieces Around the World

For art lovers and travellers alike, seeing Gustav Klimt’s works in person is an experience unlike any other. One cannot appreciate the luminosity of his gold leaf paintings, the intricate patterns, and the sheer presence of his compositions through reproductions alone. Fortunately, Klimt’s most important works reside in some of the world’s most renowned museums, with the highest concentration in Vienna, Austria, his lifelong home.

From Vienna’s grand palaces to galleries around the world, these must-visit locations showcase Klimt’s genius in all its gilded splendour.

Major Museums Featuring Klimt’s Works

1. Belvedere Palace (Vienna) – Home of The Kiss

The Upper Belvedere is the definitive destination for Klimt enthusiasts. It houses the world’s most extensive collection of Klimt paintings, including his most famous masterpiece, The Kiss (1907–1908).

- The museum’s Klimt Room also features Judith with the Head of Holofernes (1901) and several of his landscapes.

- The grand Baroque setting of the Belvedere Palace adds to the magic of seeing Klimt’s works in person.

- Must-See Factor: ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ (Essential for Klimt fans)

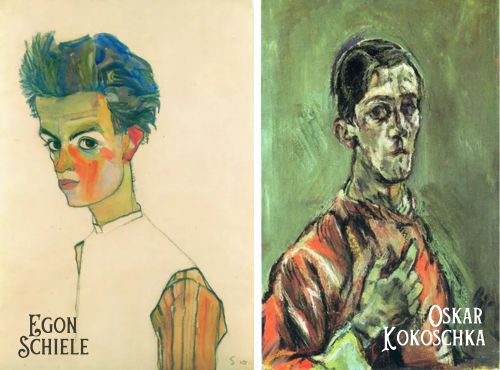

2. Leopold Museum (Vienna) – Klimt’s Early Works

Located in Vienna’s MuseumsQuartier, the Leopold Museum is best known for its collection of Egon Schiele. Still, it also features several important Klimt works, including some of his earlier and lesser-known pieces.

- Klimt’s unfinished portrait of Ria Munk, an example of his later portraiture style, is housed here.

- The museum provides a broader historical context, displaying works by other Vienna Secession artists.

- Must-See Factor: ⭐⭐⭐⭐ (Great for those interested in Klimt’s artistic evolution)

3. Neue Galerie (New York) – Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I

For those outside Europe, the Neue Galerie in New York City is the best place to see Klimt’s “Woman in Gold,” the famous Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907).

- This opulent portrait was at the centre of a landmark Nazi-looted art restitution case, later dramatized in the film Woman in Gold (2015).

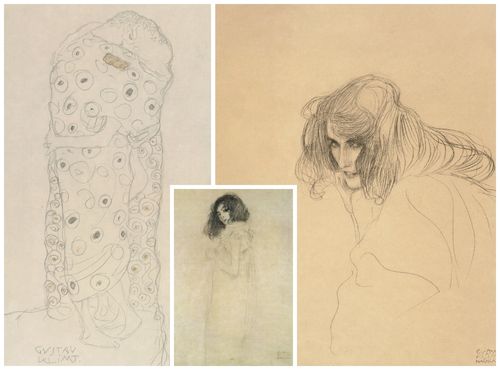

- The Neue Galerie also exhibits Klimt’s landscape paintings and preparatory sketches, offering insight into his creative process.

- Must-See Factor: ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ (Essential for understanding Klimt’s legacy and restitution history)

4. Other Notable Locations

- Secession Building (Vienna) – The Beethoven Frieze

- One of Klimt’s most expansive and symbolic works is the Beethoven Frieze (1902), a massive mural dedicated to Ludwig van Beethoven.

- The Secession Building itself is an architectural gem, crowned with a golden dome known as the “Golden Cabbage.”

- Must-See Factor: ⭐⭐⭐⭐ (Perfect for those interested in Klimt’s large-scale decorative art.)

- Albertina Museum & MAK (Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna)

- These institutions house Klimt’s drawings, sketches, and applied arts, giving a behind-the-scenes look at his process.

- The Albertina holds an extensive collection of Klimt’s preliminary sketches, including studies for his female portraits.

- Must-See Factor: ⭐⭐⭐ (For those interested in Klimt’s creative development.)

Travel Tips for Klimt Enthusiasts

Best Times to Visit the Belvedere and Secession Building

Belvedere Palace is one of Vienna’s most visited museums, and The Kiss is its star attraction.

- Best Time to Visit: Arrive early in the morning (right at opening) or late afternoon, when tour groups have thinned out.

- Pro Tip: Visit on a weekday rather than a weekend for a more peaceful experience.

Secession Building: The Beethoven Frieze is less crowded than the Belvedere, making it a great stop for those looking to appreciate Klimt’s artistry without the rush.

- Best Time to Visit: Midday or early afternoon—this museum doesn’t get as packed as the Belvedere.

Hidden Gems: Lesser-Known Klimt Works

While The Kiss and Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I are world-famous, some of Klimt’s most fascinating works can be found in smaller collections or even in private hands:

- Klimt’s landscapes and architectural paintings—often overshadowed by his portraits—are scattered across European and American collections.

- The Museum of Fine Arts (Budapest, Hungary) houses a stunning Klimt painting, Water Serpents II, which is not as widely known as his portraits.

- Private collections occasionally lend Klimt’s works to major exhibitions, making temporary Klimt retrospectives worth seeking out.

Tips for Art Lovers: How to Engage with Klimt’s Art Beyond Photography

- Take your time. Many visitors snap a quick photo and move on. Instead, step back, observe the details, textures, and brushwork, and let the painting reveal itself over time.

- Sketch or take notes. Drawing even a tiny part of Klimt’s patterns or jotting down impressions can deepen appreciation.

- Look beyond the gold. While his Golden Phase is the most famous, pay attention to each composition’s subtle colour transitions, expressive faces, and symbolic elements.

- Explore related artists. Klimt was part of a broader movement—take time to discover other Vienna Secession artists such as Egon Schiele and Koloman Moser for a fuller picture of the era.

Final Thoughts

Seeing Klimt’s masterpieces in person is a transformative experience, offering insights that no photograph or reproduction can capture. A visit to Vienna’s Belvedere Palace, an exploration of Klimt’s lesser-known works at the Leopold Museum, or an encounter with the “Woman in Gold” in New York each offers a distinct glimpse into his timeless allure.

Klimt’s Legacy & Influence

Klimt’s Impact on Modern Art & Design

Gustav Klimt’s influence extends far beyond the gilded frames of his canvases—his work has left an indelible mark on modern art, design, and even fashion. His signature use of ornamentation, sensuality, and symbolism has inspired generations of artists, from Egon Schiele and Oskar Kokoschka to contemporary painters exploring decorative abstraction.

Beyond the fine arts, Klimt’s aesthetic has permeated interior design, textiles, and fashion. The intricate, mosaic-like patterns of his Golden Phase have been translated into luxury fabrics, haute couture collections, and jewelry designs. Prominent fashion designers, including Alexander McQueen, John Galliano, and Dolce & Gabbana, have drawn from Klimt’s iconic motifs, incorporating gold leaf textures, flowing forms, and elaborate embellishments into their garments.

Even in advertising and branding, Klimt’s distinctive style is instantly recognizable. His elaborate decorative compositions have been used to sell everything from perfume to high-end home décor, proving that his aesthetic remains as alluring today as it was over a century ago. The fusion of fine art and commercial design ensures that Klimt’s artistic DNA continues to thrive in unexpected and innovative ways.

Theft & Recovery of Klimt Works

Klimt’s legacy is also intertwined with one of modern history’s most significant cases of art theft and restitution. Many of his most valuable paintings were originally owned by Jewish collectors in Vienna, whose collections were looted by the Nazis during World War II.

The most famous case involves Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, also known as The Woman in Gold. The painting was commissioned in 1907 by the wealthy Bloch-Bauer family. The Nazis seized the painting in 1938 after Austria’s annexation. It remained in Austrian state ownership for decades until a landmark legal battle led to its restitution. In 2006, after years of litigation, Maria Altmann, the niece of Adele Bloch-Bauer, successfully reclaimed the painting. The case was later dramatized in the 2015 film Woman in Gold, starring Helen Mirren.

Other Klimt paintings remain missing or contested. Works like Philosophy, Medicine, and Jurisprudence—once part of Klimt’s Faculty Paintings—were tragically destroyed in a fire set by retreating Nazi forces in 1945. Meanwhile, pieces such as Water Serpents II and Garden Path with Chickens have resurfaced in private collections but remain subjects of dispute.

These cases highlight not only the dark history of Nazi art looting but also the ongoing efforts to reclaim and restore artistic heritage. Klimt’s works, once considered controversial, are now among the most valuable paintings in the world, with Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I selling for $135 million in 2006.

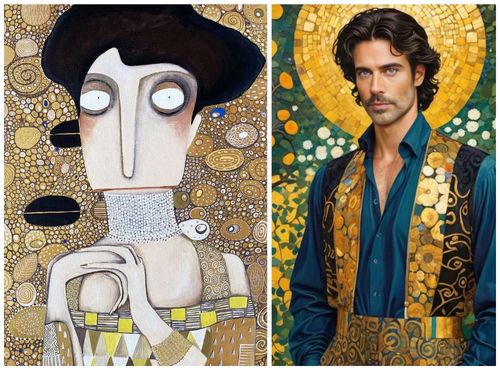

Klimt’s Enduring Popularity

Few artists have achieved the pop culture ubiquity of Gustav Klimt. The Kiss, in particular, has been endlessly reproduced on postcards, posters, scarves, mugs, and home décor, making it one of the most recognized artworks globally.

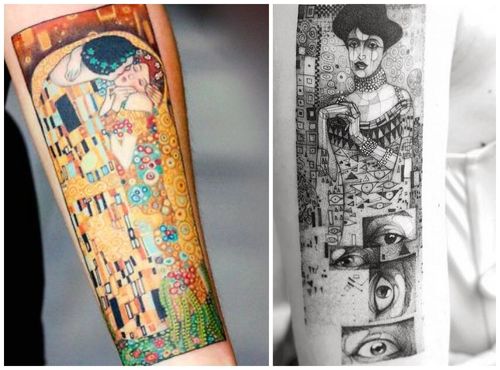

However, Klimt’s influence extends beyond traditional reproductions—his work has found new life in modern digital art, tattoo culture, and contemporary reinterpretations.

Digital artists and illustrators often incorporate Klimt-inspired golden textures and swirling compositions, blending traditional techniques with modern technology.

Tattoo artists have adapted Klimt’s intricate patterns and figurative style into stunning body art, with The Kiss being a particularly popular design.

Contemporary artists and fashion designers continue to reference Klimt’s style, from reimagining his female portraits in modern settings to using his motifs in avant-garde clothing.

More than a century after his death, Klimt’s art remains timeless, captivating new generations with its beauty, sensuality, and visionary craftsmanship. From museum exhibitions to high fashion and digital reinterpretations, Klimt’s golden world shimmers in the modern imagination.

Reflection & Conclusion

My Personal Takeaway: A Moment with the Beethoven Frieze

Standing before The Kiss at the Upper Belvedere was a dazzling experience, but it was also a shared moment with a crowd—tourists snapping photos, murmurs of conversation, and the inevitable jostling for the perfect viewing angle. Though patience was rewarded with a clearer look, the encounter remained somewhat hurried, a spectacle more than a contemplation.

In contrast, my visit to the Secession Building felt entirely different. Inside this strikingly modernist structure, beneath its famous golden dome, I found myself alone with one of Klimt’s most monumental and enigmatic works—the Beethoven Frieze.

This vast, gilded mural stretches across three walls. It seemed to envelop me, its swirling lines and ghostly figures unfolding in a silent narrative of struggle, transcendence, and artistic triumph. With few other visitors present, I had the luxury of slowing down, tracing the details with my eyes, and absorbing the work in solitude. Unlike The Kiss’s compact, intimate embrace, the Beethoven Frieze felt expansive and immersive, drawing me into Klimt’s vision of art as a pathway to spiritual liberation.

This contrast—between the celebrated and the quietly profound, the crowded and the contemplative—reinforced something I’ve come to appreciate in art and travel alike: sometimes, the less obvious encounters leave the deepest impressions.

Conclusion: The Enduring Power of Klimt

The art of Gustav Klimt is more than just beautiful—it is enigmatic, symbolic, and deeply human. Klimt’s work continues to fascinate through his golden portraits, ethereal landscapes, and provocative allegories—transcending time with its blend of sensuality, spirituality, and emotional depth.

His legacy is not confined to museums; it lives on in design, fashion, and the collective imagination. Yet, nothing compares to seeing his work in person, where the radiance of gold, the delicate textures, and the hypnotic patterns reveal their full magic.

Whether standing before The Kiss in a crowded gallery or discovering a lesser-known Klimt masterpiece in a quieter setting, the experience of his art is always a journey into beauty, mystery, and the essence of Vienna’s golden age.

What About You?

Have you ever seen Klimt’s works in person?

- What was your most memorable encounter with one of his paintings?

- Do you have a favourite Klimt masterpiece?

I’d love to hear your thoughts! Share your experiences in the comments, and let’s keep the conversation going about one of the most captivating artists of all time.

Further Reading & Resources

Related Posts on Only Anton

If you enjoyed this guide, you may also like:

- How to Get the Most Out of Your Museum Visit: A practical guide to making the most of your time in art museums, from observation techniques to avoiding museum fatigue.

- Symbolism and Iconography: Uncovering Hidden Meanings: Uncover the hidden meanings of symbolism in art. Decode themes, motifs, and famous works to deepen your appreciation of visual art.

- Vienna Highlights: A Guide to Austria’s Cultural Heart: Discover more about the city that shaped Klimt’s artistic vision, from the grand palaces to the vibrant coffeehouse culture.

External Resources

These resources offer deeper insight into Klimt’s artistic vision, historical context, and lasting influence. If you have a favourite book or documentary about Klimt, please share it in the comments!

Books

- Gustav Klimt: Complete Paintings by Tobias G. Natter (2018): A definitive collection of Klimt’s works, offering high-resolution images, detailed commentary, and historical insights into his artistic evolution. Find it at your library, browse online, or grab your copy here.

- Gustav Klimt: 1862-1918 (Taschen Basic Art Series) by Gilles Néret (2015): A compact yet thorough introduction to Klimt’s life, work, and artistic philosophy, featuring some of his most striking paintings. Check your local library, search online, or order a copy here.

- Gustav Klimt: Landscapes by Stephan Koja (2019): This book offers an in-depth exploration of Klimt’s often-overlooked landscape paintings, highlighting his unique approach to nature, colour, and composition. Discover it at your library, look it up online, or purchase your copy here.

- Gustav Klimt by Janina Nentwig (2019): A beautifully illustrated introduction to Klimt’s life, artistic evolution, and signature works, providing insights into his role in the Vienna Secession and Art Nouveau movements. See if your library has it, look online, or snag a copy here.

- The Lady in Gold: The Extraordinary Tale of Gustav Klimt’s Masterpiece, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer by Anne-Marie O’Connor (2015): The gripping story of Nazi-looted Klimt paintings and the decades-long legal battle for their return. Look it up at a local library, browse online, or buy your copy here.

Documentaries & Films

- Klimt & Schiele: Eros and Psyche (2018): Directed by Michelle Mally and written by Arianna Marelli. A beautifully shot documentary exploring the revolutionary world of Viennese modernism, focusing on Klimt, Egon Schiele, and their contemporaries, with narration by Lorenzo Richelmy and performances by Maxi Blaha and Rudolf Buchbinder.

- Woman in Gold (2015): Directed by Simon Curtis. Written by Alexi Kaye Campbell, based on real events involving Maria Altmann and E. Randol Schoenberg. A Hollywood dramatization of the legal fight to reclaim Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I from Austria’s national collection, starring Helen Mirren as Maria Altmann, Ryan Reynolds as lawyer E. Randol Schoenberg, and Daniel Brühl.

- Stealing Klimt (2007): Directed by Jane Chablani. This documentary recounts Maria Altmann’s decades-long struggle to recover five Gustav Klimt paintings stolen from her family by the Nazis in 1938, a story that inspired the 2015 film Woman in Gold.

- Exhibition on Screen: Klimt & The Kiss (2023): Directed by Ali Ray. This film delves into the creation and enduring allure of Gustav Klimt’s masterpiece The Kiss, exploring its rich symbolism and the artist’s scandalous life within the context of Vienna’s Art Nouveau movement.

Reputable Websites & Online Archives

- The Belvedere Museum: Home to The Kiss and the largest Klimt collection in the world. The site offers virtual tours, exhibition info, and scholarly articles.

- Leopold Museum: Explore the Leopold Museum’s impressive collection of Austrian art, featuring works by Egon Schiele, Gustav Klimt, and other modernist pioneers.

- Neue Galerie New York: Information about Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I and other Secessionist artworks in the gallery’s collection.

- Secession Vienna: Features details about the Beethoven Frieze and the Secession Building, Klimt’s artistic home.

- Google Arts & Culture: Gustav Klimt: A digital archive of Klimt’s artworks, allowing users to zoom in on paintings and explore related exhibitions.

Works Cited (in order of appearance)

Images used in this post are for educational and commentary purposes under Fair Use principles. Where possible, sources are credited, and permissions are obtained for licensed materials.

- Gustav Klimt, The Kiss, 1907–1908. Oil and gold leaf on canvas. Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna.

- Otto Eckmann, Cover of Jugend magazine, 1896.

- Gustav Klimt, Portrait of a Woman (Study for “Lasciviousness,” Beethoven Frieze, Secession). Drawing. Albertina Museum, Vienna.

- Gustav Klimt, Portrait of a Young Woman, 1896–97. Drawing. Private collection.

- Gustav Klimt, Standing Pair of Lovers, Seen from the Side, 1907–08. Drawing. Albertina Museum, Vienna.

- Ferdinand Hodler, Poster for the 19th Exhibition of the Vienna Secession, 1903. Leopold Museum, Vienna.

- Gustav Klimt, Beethoven Frieze, 1901–1902. Mixed media on wall. Secession Building, Vienna.

- Gustav Klimt, Philosophy, 1898–1903. Ceiling panel for the Great Hall of Vienna University. Destroyed by fire in Schloss Immendorf in 1945.

- Gustav Klimt, Medicine, 1898–1903. Ceiling panel for the Great Hall of Vienna University. Destroyed by fire in Schloss Immendorf in 1945.

- Gustav Klimt, Jurisprudence, 1898–1903. Ceiling panel for the Great Hall of Vienna University. Destroyed by fire in Schloss Immendorf in 1945.

- Unknown artist, Empress Theodora, 547. Mosaic. The Church of San Vitale, Ravenna.

- Kikukawa Eizan, Courtesan of the Ogiva Brothel, 1810–1815. Bequest of Mrs. Cora Timken Burnett / Wikimedia Commons.

- Alphonse Mucha, Poster of Sarah Bernhardt as Gismonda, 1894–95.

- Claude Monet, Madame Monet en costume Japonais (La Japonaise), 1876. Oil on canvas. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

- Vincent van Gogh, The Courtesan (after Keisai Eisen), 1887. Oil on canvas. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

- Title page of Paris Illustré, Le Japon, vol. 4, May 1886, no. 45–46. After a print of a courtesan by Kensai Eisen, 1808. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

- Odilon Redon, The Cyclops, 1898–1914. Oil on cardboard on panel. Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo.

- Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, 1907. Oil and gold leaf on canvas. Neue Galerie, New York.

- Gustav Klimt, Judith and the Head of Holofernes, 1901. Oil on canvas. Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna.

- Gustav Klimt, The Tree of Life, Stoclet Frieze, 1909. Oil on canvas. MAK, Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna.

- Gustav Klimt, Church in Cassone (Landscape with Cypresses), 1913. Oil on canvas. Private collection.

- Gustav Klimt, Water Serpents II, 1904–1907. Oil on canvas. Private collection.

- Egon Schiele, Self-Portrait with Striped Shirt, 1910. Black chalk and gouache on paper. Leopold Museum, Vienna.

- Oskar Kokoschka, Self-Portrait, 1913. Museum of Modern Art, New York.