Part Six in the Mastering Art Appreciation: From Novice to Connoisseur series

Introduction: Why Art Movements Matter

A Beginner’s Guide to Art Movements: From Representation to Abstraction is designed to help you understand how artistic styles evolved over time—how artists shifted from lifelike depictions of the world to abstract explorations of form, feeling, and idea.

To grasp that transformation, consider two sculptures. Apollo and Daphne (1622–1625) by Gian Lorenzo Bernini is a virtuosic Baroque masterpiece, swirling with motion, emotion, dramatic narrative, and technical detail. In contrast, Henry Moore’s Reclining Figure series reimagines the human form in flowing, abstract shapes, distilling essence and simplicity rather than detail. Each reflects not only its artist’s vision but also the values and aesthetics of its time.

This post is Part Six in the Mastering Art Appreciation: From Novice to Connoisseur series. It serves as a welcoming introduction to major Western art movements, tracing the path from Medieval and Renaissance representation to Modern and Abstract expression.

We’ll move chronologically through key periods, highlighting hallmark styles and major shifts, and offering practical insights to help you recognize and appreciate them. Art movements reflect not just aesthetic preferences but cultural shifts and human experiences. Understanding their evolution can deepen your appreciation of art. Whether you’re preparing for a museum visit or simply want to engage more deeply with the art you encounter, this guide is a springboard for further exploration.

Laying the Foundations: Understanding Art Periods and Styles

Before diving into the grand sweep of art history, it helps to clarify a few key terms and set expectations for the journey ahead.

Key Concepts for Beginners

An art movement refers to a group of artists working with shared goals, techniques, or philosophies during a specific time period—think Impressionism or Cubism. A style is broader, encompassing the visual characteristics of a work—such as realism, abstraction, or minimalism. An art period refers to a broader historical timeframe, like the Renaissance or the Baroque, within which multiple movements or styles may emerge. Art history is the academic study of how art has developed over time, often through these categories.

Scope and Focus

This guide focuses primarily on Western art history, tracing significant developments from the Medieval period to Modern abstraction. That said, it’s important to acknowledge the rich and sophisticated traditions of non-Western cultures—from the intricacies of Chinese brush painting to the symbolic geometry of Islamic art, the vibrant murals of Pre-Columbian civilizations, and beyond.

Encouragement Against Overwhelm

Art history is vast—spanning continents, centuries, and countless artists. No one can master it all at once, and that’s okay. For beginners, it’s better to start small. Focus on one or two periods that spark your curiosity, and gradually build your understanding from there. Let your personal interests guide your learning.

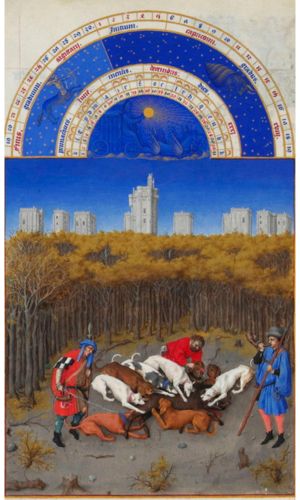

Starting with the Medieval World

To begin our chronological journey, let’s consider two works from the period just before the Renaissance. The Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (1412–1416), an illuminated manuscript by the Limbourg Brothers, is a jewel of Medieval art. It prioritizes symbolism and decorative detail over naturalism, with each page rich in narrative and seasonal imagery.

In contrast, Giotto’s Lamentation (1305) introduces something new. While still rooted in religious narrative, Giotto’s figures occupy a more believable space, showing early attempts at depth and emotional realism. His work foreshadows the Renaissance shift toward perspective, human emotion, and naturalism.

Practical Insight

Start small. Focus on one or two periods that intrigue you and explore how these movements influence your favourite artists.

The Renaissance and the Rise of Representational Art (c. 1350-1620)

The Renaissance marks a profound turning point in Western art history. Originating in Italy and spreading across Europe, this era was characterized by a renewed interest in Classical antiquity, humanism, and the natural world. Artists sought not only to imitate reality but to elevate it—combining technical innovation with philosophical ideals.

Main Features of Renaissance Art

The word “Renaissance” means “rebirth,” and this period saw the revival of ancient Greek and Roman ideas, particularly in art, architecture, and literature. Artists embraced human-centred themes and explored new ways to depict the world with clarity and depth. Linear perspective, pioneered by Filippo Brunelleschi, allowed for mathematically accurate spatial representation, while chiaroscuro (the use of light and shadow to model form) added volume and realism. Anatomical studies informed more lifelike human figures, and Classical ideals of proportion and harmony shaped both form and content.

Masterworks and Meaning

Donatello’s David (c. 1440)

Donatello’s bronze David is a pivotal work in early Renaissance sculpture. It revives the contrapposto stance of Classical statuary, showing the figure with one leg bearing weight while the other relaxes—a subtle twist that breathes life into the body. The sculpture captures a youthful and contemplative David, emphasizing human beauty and quiet strength rather than overt heroism.

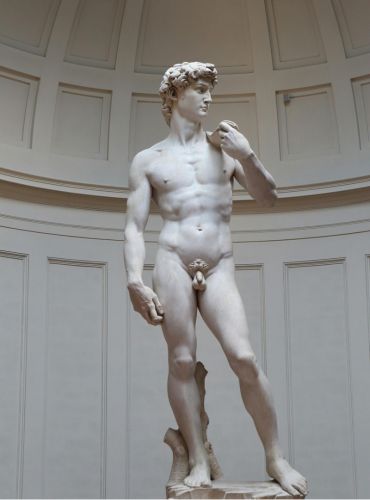

Michelangelo’s David (1504)

In contrast, Michelangelo’s marble David stands in monumental defiance, his muscles taut with tension. Larger than life in both scale and spirit, this sculpture epitomizes the High Renaissance ideal of the heroic nude, merging naturalistic precision with psychological intensity.

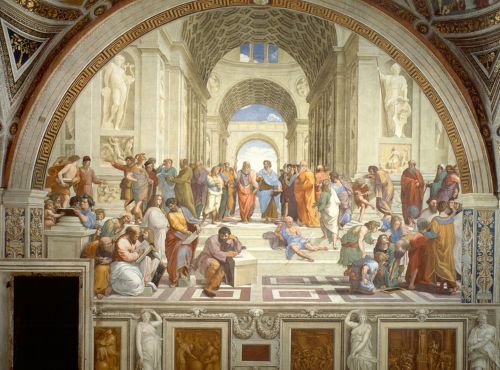

Raphael’s School of Athens (1511)

A triumph of fresco painting, The School of Athens gathers the great philosophers of antiquity—Plato, Aristotle, Socrates, and others—into a harmonious, idealized architectural space. It exemplifies balance, clarity, and intellectual grandeur.

Practical Insight: Plato points upward to the realm of Forms; Aristotle gestures toward the empirical world—two gestures, two worldviews.

Albrecht Dürer’s Self-Portrait (1500)

In Northern Europe, the Renaissance took a slightly different course. Dürer’s self-portrait presents the artist in a Christ-like pose, frontal and solemn, a striking assertion of artistic identity and intellect. His detailed rendering and symbolic composition highlight both individual expression and spiritual resonance.

Practical Insight: Consider Dürer’s Christ-like pose as a declaration of artistic dignity.

Mannerism as a Transition

As the Renaissance matured, artists began to push the Renaissance ideals to expressive extremes. Mannerism, a style that emerged in the mid-16th century, featured elongated forms, ambiguous space, and complex allegories.

• Parmigianino’s Madonna with the Long Neck distorts proportion for elegance and effect.

• Bronzino’s Venus, Cupid, Folly, and Time layers symbolism with icy precision and eroticism.

Practical Insight: Look for proportion, perspective, and balance as a hallmark of Renaissance style.

From Baroque Drama to Romantic Expression (c. 1600–1850)

As the Renaissance gave way to new spiritual and political forces, artists began exploring more dynamic, emotionally charged modes of expression. From the theatricality of the Baroque to the passion and introspection of Romanticism, this period of art history reveals how deeply emotion and ideology can shape visual culture.

Baroque: Theatrical Intensity

Emerging around 1600, the Baroque period responded directly to the Catholic Church’s Counter-Reformation, which aimed to reassert its influence through art that stirred the soul and affirmed faith. Baroque art dazzled with its theatrical compositions, dynamic movement, and intense emotional content.

A key feature of Baroque painting is tenebrism—a dramatic use of light and dark to create contrast and focus. While chiaroscuro softly models form with light and shadow, tenebrism plunges entire backgrounds into darkness to heighten the visual drama of illuminated figures. Baroque artists used these tools for technical effect and narrative power.

Caravaggio, The Calling of Saint Matthew (1600)

This famous work by Caravaggio exemplifies the Baroque approach. A shadowed tavern scene is pierced by a beam of divine light, illuminating the moment Christ calls Matthew to a spiritual awakening. The figures are rugged, real, and grounded in everyday life, making the miracle feel startlingly present.

Practical Insight: Track how light draws your attention to a moment of narrative or revelation.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1647–1652)

Bernini’s sculpture captures spiritual transcendence in marble. The saint’s swooning figure is caught in divine rapture as a cherub prepares to pierce her heart. Billowing robes, textured clouds, and hidden lighting from above create an almost cinematic intensity. The sculpture becomes a religious tableau and a theatre of divine experience.

Peter Paul Rubens, Elevation of the Cross (1610)

Rubens’ work further illustrates Baroque power. Muscular figures strain under the weight of the cross, their twisting bodies emphasizing the tension and emotion of the scene. Rubens’ bold colour palette and dynamic diagonals underscore the spiritual and physical drama of Christ’s crucifixion.

Romanticism: Sublime Emotion

By the late 18th century, Enlightenment rationality and industrialization had sparked a backlash. Romanticism emerged in response, focusing on emotion, imagination, and nature’s overwhelming power. Where the Baroque structured emotion through religious doctrine, Romanticism turned inward—toward the personal, the mystical, and the sublime.

Romantic artists explored themes of rebellion, mortality, and the supernatural. Nature was not simply scenic but awe-inspiring, even terrifying, and capable of stirring existential reflection.

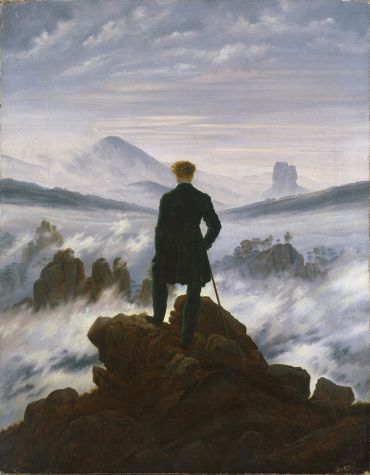

Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818)

Friedrich’s painting epitomizes this introspective sublime. A lone figure stands atop a rocky precipice, gazing over a vast, mist-covered landscape. We never see his face—only his posture, caught between presence and insignificance.

Practical Insight: Consider scale and solitude—how artists place humans in relation to overwhelming landscapes.

J.M.W. Turner, The Fighting Temeraire (1839)

Turner’s work captures a moment of technological transition. The mighty warship, once glorious, is towed by a grimy tugboat into sunset-lit waters. The painting blends light and nostalgia, exploring the costs of progress.

Albert Bierstadt, Valley of the Yosemite (1864)

Bierstadt takes the Romantic fascination with nature to an American scale. Towering cliffs and luminous skies envelop the viewer, elevating the wilderness into a sacred realm. Although Bierstadt’s work verges on the idealized, it conveys a profound spiritual reverence for untouched land.

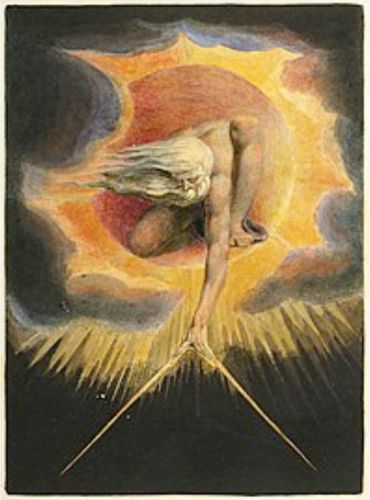

William Blake, Ancient of Days (1794)

Blake represents the visionary strain of Romanticism. This mythic figure—part god, part creator—bends within a cosmic void, measuring existence with golden compasses. Blake’s art fuses poetry, mysticism, and rebellion into singular images of cosmic wonder.

Bridging the Two

Although separated by more than a century, the Baroque and Romantic periods share a common obsession with emotional impact. Yet they diverge in purpose and tone:

- Baroque emotion is orchestrated and outward—engineered to awe, persuade, and uplift within religious and courtly settings.

- Romantic emotion is internalized—rooted in solitude, reflection, and the boundless mysteries of nature and self.

Where Baroque compositions pull you into dramatic events, Romantic works invite you to stand alone and feel their vast implications. One guides you through structured revelation; the other leaves you suspended in sublime uncertainty.

The Shift to Light and Emotion: Impressionism and Post-Impressionism (c. 1860–1905)

As the 19th century progressed, artistic movements began to respond more directly to modern life and individual perception. Following the drama of Romanticism and the moral clarity of Realism, a new generation of artists sought to capture the fleeting qualities of light, atmosphere, and emotion. Impressionism and Post-Impressionism marked a radical shift in visual language—away from historical and mythological grandeur and toward the immediacy of modern experience.

Realism as a Bridge

Before Impressionism fully blossomed, Realism emerged as a sober reaction against both Romantic idealism and the academic traditions of the past. Realist artists focused on ordinary subjects, portraying the working class and rural life without sentimentality or embellishment. They believed that art should depict the world as it truly was, not as it ought to be.

Gustave Courbet, The Stone Breakers (1849)

Gustave Courbet’s work exemplifies this ethos. The painting shows two labourers engaged in backbreaking roadwork with their faces obscured to emphasize anonymity and universality. There is no heroic flourish here—just unadorned, everyday toil.

Practical Insight: Look for unvarnished, everyday detail rather than grandeur.

However, this focus on the tangible world soon gave way to an interest in how that world was perceived—not just what was seen but how light, air, and mood shaped our experience.

Impressionism: Fleeting Moments

Impressionism burst onto the scene in the 1860s with an ambition to capture the transience of life and light. Rejecting the polished finish of academic art, Impressionists embraced visible brushstrokes, outdoor scenes, and contemporary subjects. They often painted en plein air (in the open air), seeking to render the sensory experience of a single moment.

Édouard Manet, Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (1863)

Manet challenged artistic norms not only through provocative composition—a nude woman picnicking with clothed men—but also by rejecting traditional shading and linear depth. While not a full-fledged Impressionist work, this work served as a bold precursor to the movement’s rebellious spirit.

Berthe Morisot, Summer’s Day (1879)

Morisot offers a more quintessential Impressionist experience. Two women in a rowboat drift along the lake in a haze of colour and movement. Morisot’s brisk brushwork, soft palette, and feminine subject matter reveal how Impressionism expanded artistic possibilities for women and domestic spaces.

Alfred Sisley, The Bridge at Villeneuve-la-Garenne (1872)

Sisley showcases Impressionism’s mastery of landscape. Sky, water, and architecture merge into a shimmering whole, painted with rapid strokes that echo nature’s constant motion.

Practical Insight: Examine how light plays across surfaces to evoke mood.

Impressionists turned their attention away from grand narratives and toward modernity’s quieter moments—crowded boulevards, quiet gardens, leisurely afternoons. In doing so, they transformed the everyday into a realm of poetry and perception.

Post-Impressionism: Deeper Meaning

Though united in their rejection of academic norms, the Post-Impressionists did not comprise a unified movement. Instead, they shared a desire to move beyond surface impressions and delve into structure, emotion, and symbolic meaning. They retained Impressionism’s colour and brushwork but often infused their work with personal vision or intellectual rigour.

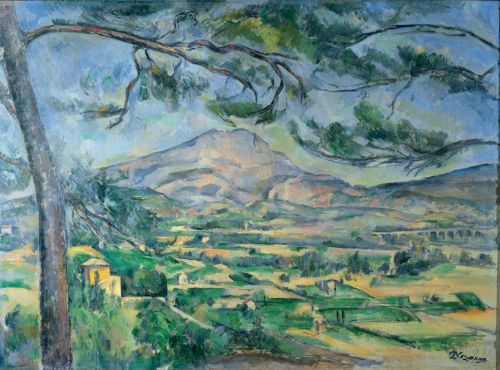

Paul Cézanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire series (1887–1906)

The work of Cézanne represents this evolution. With each rendition of Mont Sainte-Victoire, Cézanne gradually abstracted the mountain into shifting planes of colour and geometric form. His brushstrokes build volume and structure, paving the way for Cubism and modern abstraction.

Henri Rousseau, The Sleeping Gypsy (1897)

Rousseau offers a surreal, dreamlike image of a lone figure sleeping in the desert as a lion quietly sniffs nearby. The naïve style and fantastical imagery belie a quiet psychological power, evoking vulnerability, mystery, and the subconscious.

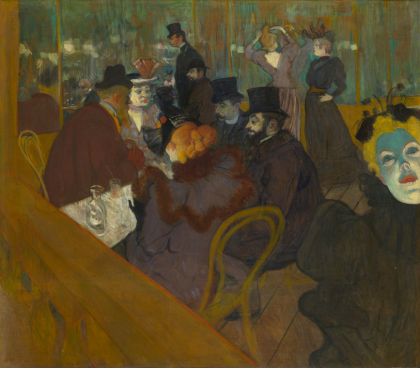

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, At the Moulin Rouge (1895)

Toulouse-Lautrec’s art plunges us into Paris’s bohemian nightlife. Bold colours, skewed perspectives, and candid portrayals of performers and patrons create a sense of energy tinged with melancholy. Toulouse-Lautrec captures both the glamour and the grit of urban decadence.

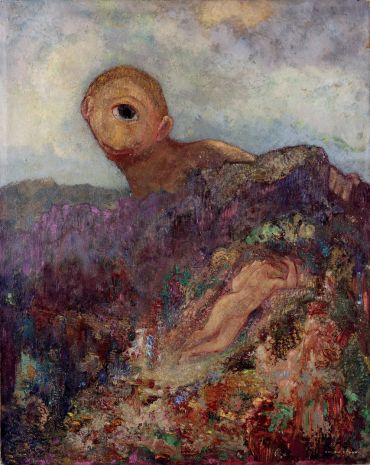

Odilon Redon, The Cyclops (1914)

Redon takes us into the realm of myth and fantasy. A lone, cyclopean figure looms above a sleeping woman in a landscape suffused with colour and symbolism. Redon’s Symbolist aesthetic invites viewers to see beyond the literal and enter a space of introspective wonder.

Practical Insight: Follow emotional undercurrents beneath colour and form.

While Impressionism celebrated what the eye could see in a fleeting moment, Post-Impressionism asked viewers to linger, interpret, and feel. Its artists opened new paths into abstraction, emotion, and philosophical exploration, preparing the ground for the seismic shifts of the 20th century.

Cubism and Modernism: Breaking the Rules of Representation (c. 1907–1960)

As the 20th century dawned, the pace of change accelerated—technologically, politically, and artistically. Traditional forms of representation no longer felt adequate to capture modern life’s fragmented, fast-moving realities. Artists sought to break from convention, not simply in subject matter but in how they perceived and constructed the world on canvas. Cubism and Modernism emerged as radical departures, redefining the very nature of artistic vision.

Cubism: Fragmenting Reality

Pioneered by Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso, Cubism challenged the Renaissance illusion of depth and the idea of a single, unified perspective. Instead, Cubism dissected objects into geometric shapes and reassembled them from multiple angles at once, offering a more conceptual, analytical view of reality.

Georges Braque, Violin and Candlestick (1910)

Braque’s painting breaks the still life into intersecting planes of gray and ochre. The violin, candlestick, and surrounding space are fractured into abstract forms as if simultaneously seen from different vantage points. Despite its abstraction, the painting invites careful reconstruction, requiring the viewer to piece together clues and recognize the familiar objects hidden in plain sight.

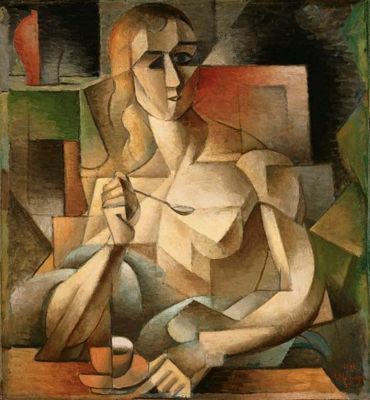

Jean Metzinger, Tea Time (1911)

Metzinger adds a burst of colour and figuration to Cubist principles. A seated woman sips tea, but her body, clothing, and surroundings are rendered in vibrant, angular patterns. Metzinger blends elegance and experimentation, showing how Cubism could be both intellectually challenging and visually engaging.

Practical Insight: Try reconstructing the subject in your mind—like a puzzle.

Cubism asked viewers not to observe a representation passively but to engage in perceiving actively. It was not just about looking but about thinking through vision.

Modernist Experiments: Redefining Art

While Cubism shattered traditional form, Modernism broadened the spectrum of what art could express. It encompassed a wide array of movements—Futurism, Constructivism, Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art—each pushing artistic boundaries in new ways. What united them was a shared interest in innovation, abstraction, and often, a critique of tradition.

Paul Klee, Senecio (1922)

Klee’s work distills the human face into geometric shapes—squares, circles, and triangles—painted in bold, contrasting colours. It is both a portrait and a meditation on identity, blending abstraction with psychological resonance. Klee’s work speaks to the Modernist desire to reach deeper emotional or intellectual truths beyond surface appearances.

Umberto Boccioni, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913)

Boccioni captures the energy of the machine age. A stylized human figure strides forward, its body stretched and flowing like wind through fabric. This Futurist sculpture does not just represent movement—it becomes movement. It celebrates speed, power, and the forward momentum of modern life.

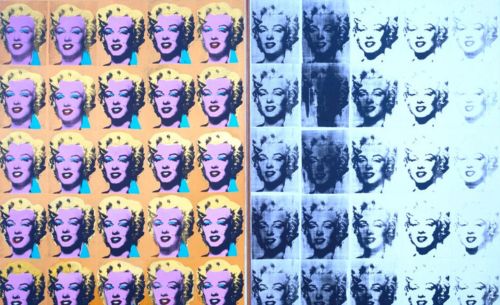

Andy Warhol, Marilyn Diptych (1962)

Warhol’s Pop Art offers a very different kind of Modernist expression. Repeating the iconic face of Marilyn Monroe across two panels—one in vibrant colour, the other fading into black and white—Warhol merges celebrity, consumerism, and mass production. His silkscreen printing blurs the line between original art and mechanical reproduction, turning pop culture into subject and medium.

Practical Insight: Consider what deeper idea or emotion lies beneath the surface.

Modernism expanded the vocabulary of art, making room for wit, irony, sorrow, and spirituality. Whether abstract or figurative, its works ask not only to be seen but also interpreted.

From the fractured forms of Cubism to the bold provocations of Modernism, early 20th-century artists reimagined art as a space for exploration—of perception, identity, society, and thought. These movements paved the way for even more radical departures in the decades to follow as the very definition of art continued to evolve.

The Leap to Abstraction: Colour, Form, and Feeling (c. 1910–1960s)

As the 20th century progressed, artists began to ask: What if art did not have to represent anything at all? What if its power lay not in depiction but in evocation? The leap to abstraction marked one of the boldest turns in art history—a deliberate move away from recognizable subjects toward the pure elements of art: form, colour, line, texture, and scale. For some artists, abstraction became a spiritual language; for others, it was a formal and intellectual exploration. Either way, the question was no longer “What is this?” but “What does this make me feel?”

Beyond Representation

While earlier movements like Post-Impressionism and Cubism had flirted with abstraction, artists such as Wassily Kandinsky, Frank Stella, and Mark Rothko fully embraced it. They believed that non-representational art could express emotion, rhythm, harmony—even transcendence—more directly than traditional narrative painting. The canvas became a stage for sensation, not storytelling.

Wassily Kandinsky, Composition VII (1913)

Widely regarded as one of the first truly abstract masterpieces, Kandinsky’s Composition VII is a chaotic, swirling explosion of colour and form. Lines loop and intersect like musical phrases, creating a visual symphony that reflects his deep interest in the connection between painting and music. Kandinsky believed that colour had inherent emotional and spiritual properties, and he used them deliberately to stir the soul.

Practical Insight: Let go of the search for subject. Let the colour and scale speak.

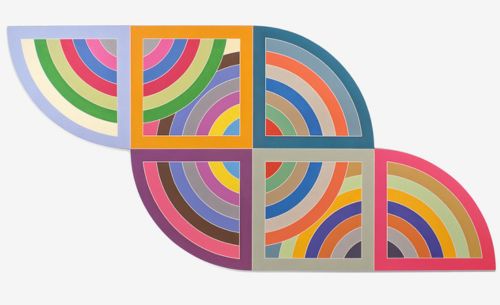

Frank Stella, Harran II (1967)

In contrast to Kandinsky’s lyrical abstraction, Frank Stella’s Harran II exemplifies Minimalism and geometric clarity. A large, radiating pattern of interlocking arcs painted in vivid colours, the work exudes precision and repetition. It doesn’t aim to represent anything beyond itself—it simply is. Stella famously said, “What you see is what you see,” emphasizing direct engagement with colour, form, and structure.

Practical Insight: Notice how geometry and colour can create rhythm and balance without a central subject.

Mark Rothko, No. 14 (1960)

With Mark Rothko, abstraction becomes immersive. His monumental painting, No. 14, is composed of large, soft-edged rectangles in luminous red and violet tones suspended in a glowing field. It invites slow contemplation. Stand before it, and you may find yourself enveloped in colour, emotion, and silence. Rothko wasn’t painting things—he was painting states of being.

Practical Insight: Stand back. Let yourself be absorbed into the atmosphere. Don’t think—just feel.

By abandoning representational anchors, abstract artists opened the door to personal interpretation. These works challenge us not to decode a scene but to experience a mood. They invite an inner dialogue where meaning is not fixed but discovered anew by each viewer.

Practical Advice for Exploring Art Movements

By now, you’ve journeyed from the luminous realism of the Renaissance to the evocative abstraction of the 20th century. But knowing art history is only part of the equation. Genuine appreciation comes from engaging with art in real time, whether in a museum, gallery, book, or online collection. The following strategies are designed to help you cultivate a more personal, rewarding relationship with art that evolves over time and encourages curiosity and reflection.

1. Visit Museums Strategically

Large museums can overwhelm even seasoned visitors. Rather than trying to see everything in one visit, choose one or two movements or periods that intrigue you. For example, spend an hour exploring just the Baroque galleries or seek out the Impressionists you love. Let yourself dwell in front of just a few works—quality over quantity.

Tip: Museums often offer maps, highlights tours, or thematic routes. These tools can help you navigate with intention.

2. Stretch Your Comfort Zone

It’s natural to gravitate toward art that resonates immediately, whether it’s serene landscapes or heroic sculpture. But sometimes, the most rewarding insights come from engaging with works that initially confuse or repel you. If you love Renaissance harmony, try spending time with a Cubist painting. Ask yourself: Why do I resist this? What might it be trying to say?

Art becomes richer when you challenge your assumptions.

3. Compare Across Cultures

Art movements are not monolithic. Impressionism in France has a different flavour than in America or Japan. Expressionism looks different in Germany than it does in Mexico. As you explore, look for regional interpretations of the same movement. What cultural or political forces shaped these variations? This comparison helps you appreciate art not just as a style but as a conversation between artists and their world.

4. Zoom In

Sometimes, the magic of a painting lies not in its grand themes but in the small details. Get close. Examine the brushwork, the layering of colour, and the texture of a surface. Try to sense the artist’s hand, their energy, and their revisions. These tactile moments bring you face-to-face with the act of creation itself.

5. Reflect and Engage

Art appreciation deepens with time and reflection. Keep a journal of artworks that moved or puzzled you. Revisit your favourite pieces to see how your perspective has changed. Share your impressions in discussion groups, online forums, or with fellow travellers. You don’t need a degree to have a voice in the world of art.

Practical Insight: Art appreciation isn’t a race. It’s a lifelong dialogue.

Conclusion

From the harmonious realism of the Renaissance to the bold experiments of Modernism and the silent power of abstraction, art movements trace a profound human journey—one shaped by changing philosophies, technologies, and worldviews. Each era responds to its historical moment, yet each artwork invites us into a personal encounter, challenging us to see more deeply and feel more fully.

This guide has walked you through one evolutionary path of Western art, emphasizing how styles gradually moved away from direct representation toward expressive and conceptual abstraction. Along the way, we’ve examined how artists use line, form, colour, and symbolism to depict the world and shape how we understand it.

The Takeaway

Art movements are more than stylistic shifts. They reflect human values, creativity, and the urge to understand our place in the world. As you explore them, you’re not just learning history—you’re entering a conversation that spans centuries.

Whether you’re new to art or returning with fresh eyes, remember that your appreciation doesn’t need to be perfect. It only needs to be honest. Be curious. Be open. Visit a museum or browse an online gallery and see what speaks to you.

What About You?

What kinds of artworks catch your attention? Do you gravitate toward the calm symmetry of Renaissance paintings, the emotion of Romanticism, or the mystery of abstraction? Are there movements you’ve never explored—or ones you’ve dismissed but now feel curious about?

Take a moment to reflect: What do you respond to in art—and why?

Feel free to share your thoughts in the comments below or strike up a conversation with a fellow art lover. Art becomes more meaningful when it’s shared, questioned, and explored together.

Let your journey into art appreciation continue—one movement, one insight, and one moment of connection at a time.

Further Reading and Resources

If you’re inspired to keep exploring, here are some curated resources—starting with related posts from the Only Anton blog and followed by trusted external guides and readings.

Related Posts on Only Anton

- How to Get the Most Out of Your Museum Visit: Learn how to appreciate art like a pro with tips on planning your visit, engaging with artworks, and avoiding museum fatigue.

- Exploring Composition: The Foundation of Visual Art: Master the basics of art composition by exploring key elements and principles. Understand how structure guides the eye.

- The Magic of Colour: Understanding Colour Theory in Art: Discover how colour creates harmony and evokes emotions. Learn to see how artists use colour to shape meaning.

- The Artist’s Hand at Work: Brushwork and Techniques: Explore how brushwork reveals an artist’s intent. Learn about materials, mark-making, and famous examples.

- Symbolism and Iconography: Uncovering Hidden Meanings: Decode themes, motifs, and visual metaphors that deepen your understanding of historical and modern artworks.

External Resources

Books

- The Story of Art by E.H. Gombrich (2023 updated version): A classic and highly accessible introduction to Western art history, beloved by art students and general readers alike. Find it at your library, browse online, or grab your copy here.

- Art: A World History by Elke Linda Buchholz etal. (2007): A richly illustrated and concise visual guide that spans movements, techniques, and key works. Check your local library, search online, or order a copy here.

- The Annotated Mona Lisa by Carol Strickland (2018): An engaging overview of art history with sidebars, timelines, and explanations perfect for beginners. Discover it at your library, look it up online, or purchase your copy here.

Websites

- The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History: Scholarly essays, thematic explorations, and artwork timelines from one of the world’s premier museums.

- Tate’s Art Terms Glossary: A straightforward glossary of movements, styles, and techniques, with examples from the Tate’s collection.

- Smarthistory: A nonprofit platform offering videos and essays on global art history, developed by art historians and educators.

Works Cited (in order of appearance)

Images used in this post are for educational and commentary purposes under Fair Use principles. Where possible, sources are credited, and permissions are obtained for licensed materials.

Introduction

- Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Apollo and Daphne, 1622–1625. Marble. Galleria Borghese, Rome.

- Henry Moore, Reclining Figure, 1935–36. Elm wood. Buffalo AKG Art Museum, Buffalo.

Laying the Foundations

- Limbourg Brothers, Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, 1412–1416. Illuminated manuscript. Musée Condé, Chantilly, France.

- Giotto di Bondone, Lamentation, 1304–1306. Fresco. Scrovegni Chapel, Padua.

Renaissance and Mannerism

- Donatello, David, c. 1440s. Bronze. Palazzo del Bargello, Florence.

- Michelangelo, David, 1501–1504. Marble. Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence.

- Raphael, School of Athens, 1509–1511. Fresco. Apostolic Palace, Vatican Museums, Vatican City.

- Albrecht Dürer, Self-Portrait, 1500. Oil on panel. Alte Pinakothek, Munich.

- Parmigianino, Madonna with the Long Neck, 1535–1540. Oil on wood. Uffizi, Florence.

- Agnolo Bronzino, Venus, Cupid, Folly, and Time, c. 1545. Oil on wood. National Gallery, London.

Baroque and Romanticism

- Caravaggio, The Calling of Saint Matthew, 1599–1600. Oil on canvas. San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome.

- Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, 1647–1652. Marble. Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome.

- Peter Paul Rubens, The Elevation of the Cross, 1610–1611. Oil on wood. Cathedral of Our Lady, Antwerp.

- Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, 1818. Oil on canvas. Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg.

- J.M.W. Turner, The Fighting Temeraire, 1839. Oil on canvas. National Gallery, London.

- Albert Bierstadt, Valley of the Yosemite, 1864. Oil on paperboard. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

- William Blake, The Ancient of Days in Europe a Prophecy (Copy D), 1794. Hand-coloured print. British Museum, London.

Realism, Impressionism, and Post-Impressionism

- Gustave Courbet, The Stone Breakers (Les Casseurs de pierres), 1849. Oil on canvas. Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden.

- Édouard Manet, Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, 1863. Oil on canvas. Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

- Berthe Morisot, Summer’s Day, 1879. Oil on canvas. National Gallery, London.

- Alfred Sisley, The Bridge at Villeneuve-la-Garenne, 1872. Oil on canvas. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

- Paul Cézanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire, c. 1890. Oil on canvas. Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

- Henri Rousseau, The Sleeping Gypsy, 1897. Oil on canvas. Museum of Modern Art, New York City.

- Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, At the Moulin Rouge, 1892–1895. Oil on canvas. Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago.

- Odilon Redon, The Cyclops, 1898–1914. Oil on cardboard on panel. Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands.

Cubism and Modernism

- Georges Braque, Violin and Candlestick, 1910. Oil on canvas. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco.

- Jean Metzinger, Tea Time (Le Gouter), 1911. Oil on cardboard. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia.

- Paul Klee, Senecio, 1922. Oil on canvas. Kunstmuseum Basel, Basel, Switzerland.

- Umberto Boccioni, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, 1913. Bronze. Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Universidade de São Paulo.

- Andy Warhol, Marilyn Diptych, 1962. Silkscreen ink and acrylic paint on canvas. Tate, London.

Abstract Art

- Wassily Kandinsky, Composition VII, 1913. Oil on canvas. Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

- Frank Stella, Harran II, 1967. Polymer and fluorescent polymer paint on canvas. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York City.

- Mark Rothko, No. 14, 1960. Oil on canvas. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco.