Part Four of the Mastering Art Appreciation: From Novice to Connoisseur series

Introduction

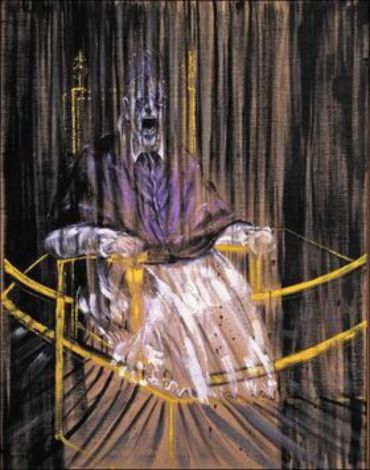

Brushwork is the artist’s signature, a visible trace of the hand at work that transforms mere materials into powerful works of art. Nowhere is this more evident than in Diego Velázquez’s Pope Innocent X (1650) and Francis Bacon’s Study After Velázquez’s Pope Innocent X (1953). Though both depict the same subject, their radically different brushwork leads to vastly different experiences. Velázquez’s masterful, smooth strokes project lifelike authority. Meanwhile, Bacon’s aggressive, distorted marks create an atmosphere of existential dread.

In this installment, Part Four in the Mastering Art Appreciation: From Novice to Connoisseur series, I’ll explore how brushwork defines an artist’s style and shapes the emotional power of a painting. I’ll examine key types of brushwork, from bold and expressive strokes to invisible, seamless techniques. I’ll also delve into how artists use brush techniques across various media, such as oil, watercolour, and acrylic. Finally, I’ll analyze iconic works by masters like Egon Schiele, John Singer Sargent, and Willem de Kooning to see how their brushstrokes breathe life into canvas. By the end, you’ll have a deeper appreciation for the artist’s hand at work.

Section I: Understanding Brushwork

Brushwork is the heartbeat of a painting—the artist’s visible touch that defines a work’s mood, texture, and emotional resonance. Whether smooth and polished or raw and energetic, brushstrokes shape how we experience art on both technical and emotional levels.

What Is Brushwork?

Brushwork refers to the visible marks left by an artist’s tools on a surface. These marks vary in size, direction, and texture, shaping how we perceive a painting’s movement, texture, and emotional tone. Brushwork is a kind of language. Smooth, precise strokes may evoke calm and control. Aggressive, spontaneous marks can suggest intensity, passion, or chaos.

Types of Brushwork

1. Bold and Expressive Brushwork

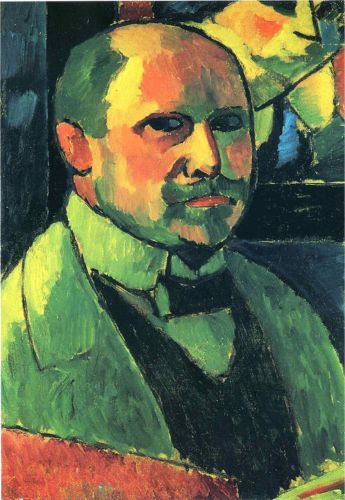

Example: Alexej von Jawlensky, Self-Portrait (1912)

Why It Works:

- Jawlensky’s thick, structured strokes create an intense emotional presence through vivid, symbolic colours. His assertive marks emphasize spiritual depth and inner emotion.

Practical Tip:

- Look for the balance between intentional, thick brushstrokes and symbolic colour arrangements that seem almost sculpted on the canvas.

2. Smooth and Invisible Brushwork

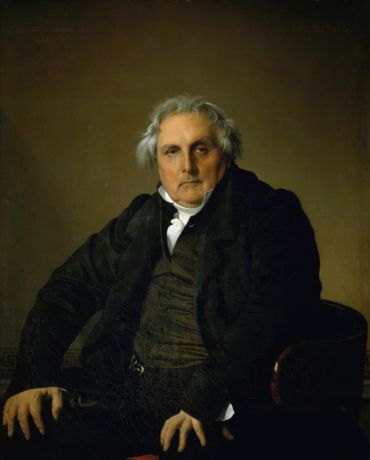

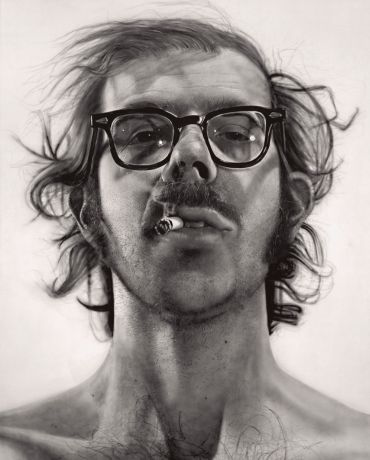

Examples: Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Portrait of Monsieur Bertin (1832) and Chuck Close, Self-Portrait (1968)

Why It Works:

- Ingres: His Portrait of Monsieur Bertin demonstrates Neoclassical perfection, with every feature seamlessly blended into a polished, lifelike finish.

- Close: In his hyperrealist Self-Portrait, Close hides the painter’s hand through innovative airbrushing, scraping, and layering, producing a photographic effect.

Practical Tip:

- Compare how both artists conceal visible strokes while achieving dramatically different styles—one through academic precision and the other through technological innovation.

3. Pointillism/Dotted Brushwork

Example: Camille Pissarro, The Boulevard Montmartre at Night (1897)

Why It Works:

- Pissarro’s short, dotted brushstrokes create shimmering urban light effects, blending colours optically in the viewer’s eye. The painting’s vibrancy emerges through countless tiny, distinct dabs of paint.

Practical Tip:

- Step back from Pointillist works to see how distinct dots dissolve into a cohesive, glowing scene. Look closely to observe the contrasting hues used for highlights and shadows.

4. Gestural Brushwork

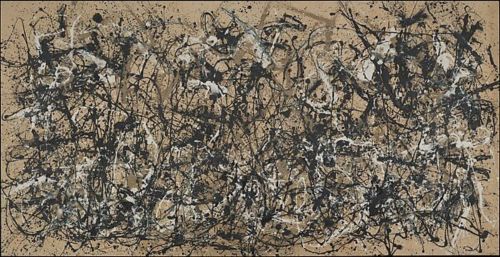

Example: Jackson Pollock, Autumn Rhythm (Number 30) (1950)

Why It Works:

- Pollock’s energetic drip technique emphasizes movement, process, and physical engagement with the canvas. His web of interlaced lines appears chaotic but reflects a dynamic, intentional rhythm.

Practical Tip:

- Consider how Pollock’s fluid, overlapping lines seem spontaneous but follow an underlying structure, suggesting both movement and intensity. His brushwork evidences the act of creation itself.

Techniques for Different Effects

Artists use a wide range of techniques to create specific effects, from precise naturalism to dynamic abstraction:

Naturalism or Representationalism:

- Glazing and Blending: Techniques that create smooth transitions of light and colour, enhancing depth and realism.

- Sfumato: A technique famously used by Leonardo da Vinci, where edges appear soft and smoky.

- Grisaille: A monochromatic method of underpainting used to create sculptural effects.

Abstraction:

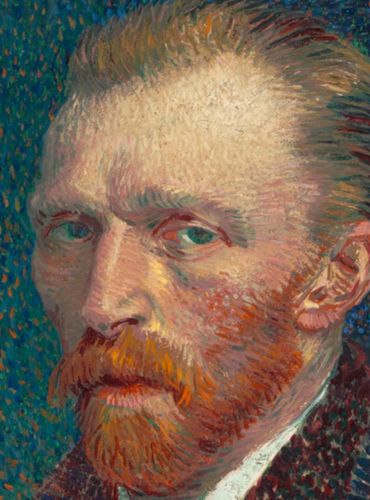

- Methods like impasto (thickly applied paint) and gestural marks create energy, texture, and movement. Van Gogh’s works exemplify impasto through bold, dimensional strokes.

Unusual Tools:

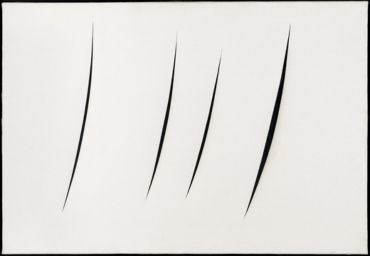

- Artists sometimes abandon brushes entirely, using palette knives, fingers, or even blades to create unconventional textures. Lucio Fontana famously slashed his canvases, turning the act of painting into a performance.

This dynamic interplay of brushwork and technique shapes how we connect emotionally, visually, and intellectually with art. Whether fluid or precise, visible or concealed, brushstrokes reveal the artist’s creative hand at work.

Section II: Techniques Across Media

Throughout history, artists have used various painting media, each offering unique possibilities for texture, depth, and expression. The medium an artist chooses can shape a work’s overall look and feel, from richly layered oil paintings to bold, modern acrylics. Here’s a closer look at some key media and the techniques that define them.

Oil Painting

Example: Rembrandt, The Night Watch (1642)

Artists have long prized oil paint for its richness, flexibility, and slow drying time, qualities which allow for blending and detailed corrections. A master of oil painting techniques, Rembrandt used chiaroscuro—the dramatic contrast of light and dark—to create depth and focus in The Night Watch.

Key Technique: Chiaroscuro:

- This method enhances three-dimensionality by using stark contrasts between highlights and shadows. Rembrandt layered translucent glazes (thin washes of oil paint) to build luminous skin tones and glowing light effects, drawing the viewer’s eye to key figures.

Watercolour

Example: J.M.W. Turner, The Blue Rigi (1842)

Watercolour is known for its fluid, transparent qualities, creating luminous and atmospheric effects. Turner’s The Blue Rigi exemplifies this with its dreamlike landscape rendered through loose washes of colour that blend seamlessly across the paper.

Key Techniques:

- Wet-on-wet: Applying colour to damp paper for soft, flowing transitions.

- Dry brush: Using a nearly dry brush for sharp, textured edges.

- Layering washes: Gradually building intensity with multiple translucent layers.

Acrylic

Example: David Hockney, A Bigger Splash (1967)

Acrylic paint, developed in the 20th century, is versatile, fast-drying, and highly pigmented. Hockney’s A Bigger Splash showcases acrylic’s ability to create flat, vibrant planes of colour with crisp edges. The painting’s smooth, artificial-looking surfaces perfectly complement its depiction of modern life.

Key Techniques:

- Hard-edge painting: Using masking tape or precise brushwork for sharp, defined edges.

- Layering: Acrylic dries quickly, allowing for fast overpainting.

- Blending and Texturing: Acrylic can mimic oil’s richness or watercolour’s softness when thinned or mixed with gels.

Mixed Media

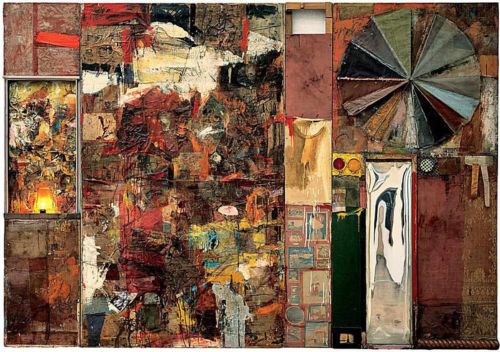

Example: Robert Rauschenberg, Combines (1954–1964)

Mixed media art incorporates diverse materials, from traditional paint to found objects and collage elements. Rauschenberg’s Combines blur the boundaries between painting, sculpture, and assemblage, redefining what art can be.

Key Techniques:

- Collage and Assemblage: Layering disparate materials like newspaper clippings, photographs, and paint.

- Experimentation: Emphasizing creative process and unconventional combinations.

Other Media

Egg Tempera

Example: Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus (c. 1484–86)

Egg tempera, made from pigment mixed with egg yolk, dries quickly to a durable, matte finish. Botticelli used fine, linear strokes for exquisite detail in The Birth of Venus, creating flowing hair and intricate fabrics.

Key Technique: Hatching and Crosshatching: Layering tiny, controlled strokes to build form and shading.

Encaustic

Example: Fayum Mummy Portraits (c. 100–300 AD)

Encaustic painting uses pigment mixed with hot wax, resulting in richly textured, luminous surfaces. Due to this technique’s durability, the ancient Fayum mummy portraits’ lifelike faces still shine with remarkable vibrancy.

Key Technique: Layering and Fusing: Artists applied molten wax in layers, fusing them with heat to create smooth or textured finishes.

Frescoes

Example: Michelangelo, The Sistine Chapel (1508–1512)

Fresco painting involves applying pigment onto wet plaster, creating a long-lasting, integrated surface. Michelangelo’s monumental Sistine Chapel ceiling demonstrates masterful fresco technique, with bold, lifelike figures seeming to leap from the ceiling’s curves.

Key Technique: Buon Fresco (True Fresco): Painting directly onto freshly applied wet plaster, ensuring pigment bonds with the wall.

Each painting medium brings unique challenges and creative opportunities, whether through oil’s glowing richness or acrylic’s modern precision. Artists choose their media intentionally, shaping how their works look and how they resonate with viewers.

Section III: Analyzing Brushwork in Famous Works

Brushwork reveals the artist’s creative process, transforming paint into something deeply expressive, dynamic, or even confrontational. In this section, we’ll explore four iconic works, each showcasing how brushstrokes uniquely communicate emotion, texture, and narrative.

Egon Schiele, Self-Portrait with Physalis (1912)

Schiele’s Self-Portrait with Physalis is an intense psychological study. Its jagged brushstrokes practically vibrate with emotional energy. His charged, angular marks create a sense of restlessness and vulnerability, emphasizing the psychological complexity of the self. The stark contrasts of warm, earthy tones against pale, ghostly skin suggest both vitality and decay, reflecting Schiele’s turbulent inner world.

Why It Works:

- Schiele’s expressive lines cut sharply through the surface, making even negative space feel aggressive and charged. His rough, uneven application of paint enhances the work’s emotional urgency, making the viewer feel the intensity of his introspection.

Practical Tip:

- Look closely at how Schiele uses exaggerated contours and uneven colour fields to create emotional tension, turning brushstrokes into symbols of psychological unrest.

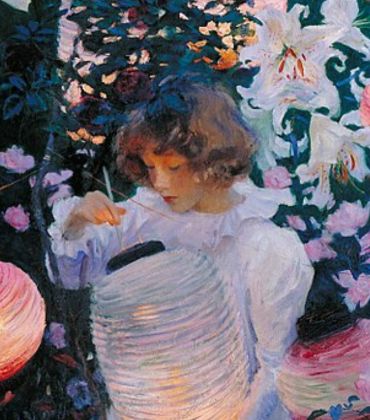

John Singer Sargent, Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose (1885–86)

Sargent’s Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose radiates a serene beauty, capturing a tranquil garden scene at dusk. His brushwork combines delicate blending with lively, visible strokes that give the flowers and foliage a soft, glowing texture. Sargent’s technical mastery lies in how he blends light and shadow while retaining a painterly quality that never feels static or overworked.

Why It Works:

- The glowing lanterns seem to shimmer with real light thanks to Sargent’s multi-layered, fluid brushstrokes. He carefully balances refined detail with spontaneous-looking strokes. The result is a scene that feels both meticulously crafted and enchantingly natural.

Practical Tip:

- Observe how Sargent’s confident blending creates the illusion of dappled light. His ability to suggest movement through subtle brushwork is key to the work’s lifelike atmosphere.

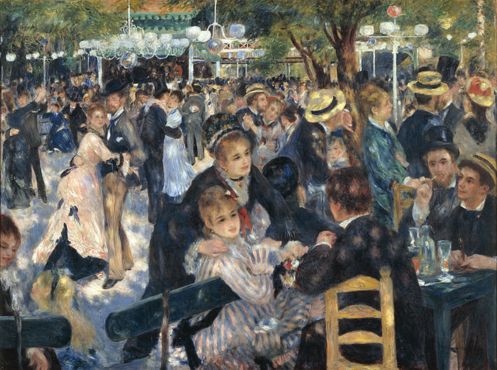

Auguste Renoir, Bal du moulin de la Galette (1876)

Renoir’s Bal du moulin de la Galette is a masterpiece of shimmering light, bustling movement, and joyful humanity. His quick, broken brushstrokes create a flickering effect, capturing the lively atmosphere of the Parisian dance hall. Fabrics, faces, and even foliage seem to sparkle under the play of sunlight filtering through the trees.

Why It Works:

- Renoir’s light-infused strokes create a dynamic sense of presence. He masterfully suggests motion through quick dabs of colour, blending forms just enough to keep the composition fluid yet defined. This technique makes the viewer feel as though they are part of the festive crowd.

Practical Tip:

- Focus on how Renoir uses light-filled highlights on faces and clothing. His deliberate softness enhances the feeling of warmth, vitality, and celebration.

Willem de Kooning, Woman I (1950–52)

De Kooning’s Woman I is an explosive collision of abstraction and representation. His gestural brushstrokes slash across the canvas, creating a violent, raw energy. The figure of the woman seems to emerge and disintegrate simultaneously, a chaotic fusion of creation and destruction. De Kooning’s aggressive, overlapping marks suggest a constant struggle between control and spontaneity.

Why It Works:

- The intense, layered brushstrokes reflect de Kooning’s physical engagement with the canvas. His visceral marks seem impulsive yet deeply considered. The technique evokes themes of power, tension, and transformation. Woman I feels alive, constantly in flux, never fully settled.

Practical Tip:

- Consider how de Kooning’s overlapping, aggressive marks build tension and depth. His expressive style forces the viewer to confront the raw, unfinished quality of the human experience.

These four masterpieces highlight the immense variety and power of brushwork in art. Brushstrokes, whether precise or forceful, subtle or bold, serve as the artist’s unique signature and can create profound emotional and visual resonance.

Conclusion: The Power of Brushwork

Brushwork is far more than a technical skill. It’s the visible signature of an artist’s creative process, revealing intent, emotion, and narrative style. We can see the fierce intensity of Willem de Kooning’s Woman I. We sense the shimmering elegance of John Singer Sargent’s Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose. The urgent psychological depth of Egon Schiele’s Self-Portrait with Physalis. Brushstrokes are what bring these works to life. From precise, seamless blending to bold, expressive marks, brushwork shapes how we connect with art on a visceral level.

Practical Advice for Observing Brushwork

To deepen your appreciation of brushwork in art:

- Look closely at textures and how brushstrokes evolve across the canvas—smooth or rough, controlled or spontaneous.

- Compare techniques between works of similar or different art movements to see how artists respond to changing styles and cultural contexts.

- Explore works in person whenever possible. Photographs can’t fully capture the tactile depth and texture of brushstrokes.

The next time you stand before a painting, let the artist’s hand guide your eye and imagination, transforming what you see into something profoundly felt.

What About You?

Have you ever noticed expressive or subtle brushwork in artworks that caught your attention? Do you prefer bold, visible strokes that radiate energy or smooth, blended techniques that create lifelike realism?

We’d love to hear from you! Share your favourite examples of brushwork or artistic techniques in the comments below. What works of art have left a lasting impression because of how they were painted?

Be sure to return to Only Anton for the next installment in the Mastering Art Appreciation series: “Symbolism and Iconography: Uncovering Hidden Meanings.” Discover how artists use symbols and visual metaphors to convey stories, emotions, and cultural messages across time and traditions.

Further Reading and Resources

For more on art appreciation and artistic techniques, check out these related posts on Only Anton:

- How to Get the Most Out of Your Museum Visit: Tips for enhancing your museum experiences.

- Exploring Composition: The Foundation of Visual Art: Learn how artists structure their works for visual impact.

- The Magic of Colour: Understanding Colour Theory in Art: Discover how colour choices shape mood and meaning in art.

External Resources

These resources will deepen your understanding of artistic techniques and brushwork, helping you see artworks with a more informed and appreciative eye.

Books

- The Work of Art: How Something Comes From Nothing by Adam Moss (2024): A thoughtful exploration of the creative process and artistic intention. Find it at your library, browse online, or grab your own copy here.

- Brushwork Essentials: How to Render Expressive Form and Texture With Every Stroke by Mark Christopher Weber (2020): A comprehensive guide on mastering brush techniques. Check your local library, search online, or order a copy right here.

- Renaissance Painting Techniques That Every Painter Should Know by Clintond J. Hill (2023): Unlock the secrets of Old Master painting methods. Discover it at your library, look it up online, or purchase your own copy here.

- Techniques in Painting: Learning from the Dutch Masters by Brigid Marlin (2022): Insights into classical painting techniques used by Dutch Golden Age artists. Find it at your library, browse online, or grab your own copy here.

- How to Paint Like the Old Masters: Watson-Guptill 25th Anniversary Edition (1983): A timeless guide on recreating masterful styles and techniques. Explore it at a nearby library, search the web, or buy it directly here.

- Lessons in Classical Painting: Essential Techniques from Inside the Atelier by Juliette Aristides (2016): A detailed look at classical art training and traditional painting skills. See if your library has it, look online, or snag a copy here.

Articles

- “How to Paint Looser: Mastering Brushwork Techniques for Impressionist Art” by Will Kemp: A practical guide on creating dynamic and expressive brushwork. Read the article here.

- “Brushwork and the Breath” by Katie Swatland, Realism Today: Explore how mindful brushwork can enhance realism and artistic flow. Find the article here.

Works Cited (in order of appearance)

Images used in this post are for educational and commentary purposes under Fair Use principles. Sources are credited, and permissions are obtained for licensed materials where possible.

Introduction

Diego Velázquez, Pope Innocent X, 1650. Oil on canvas. Collection of the Galleria Doria Pamphilj, Rome.

Francis Bacon, Study After Velázquez’s Pope Innocent X, 1953. Oil on canvas. Des Moines Art Center, Iowa.

Section I

Alexej von Jawlensky, Self-Portrait, 1912. Oil on canvas. Collection of the Kunstmuseum Basel, Switzerland.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Portrait of Monsieur Bertin, 1832. Oil on canvas. Musée du Louvre, Paris.

Chuck Close, Self-Portrait, 1968. Acrylic on canvas. Collection of the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis.

Camille Pissarro, The Boulevard Montmartre at Night, 1897. Oil on canvas. National Gallery, London.

Jackson Pollock, Autumn Rhythm (Number 30), 1950. Enamel on canvas. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Leonardo da Vinci, Mona Lisa, 1503–1519. Oil on panel. Collection of the Musée du Louvre, Paris.

Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait, 1887. Oil on artist’s board. Joseph Winterbotham Collection, Art Institute of Chicago.

Lucio Fontana, Concetto Spaziale, Attese, 1960. Oil on canvas. AKG Art Museum, Buffalo, NY.

Section II

Rembrandt van Rijn, The Night Watch, 1642. Oil on canvas. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

J.M.W. Turner, The Blue Rigi, 1842. Watercolour on paper. Tate Britain, London.

David Hockney, A Bigger Splash, 1967. Acrylic on canvas. Tate Modern, London.

Robert Rauschenberg, Charlene, 1954. Mixed media. Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam.

Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus, c. 1484–86. Tempera on canvas. Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

Mummy Portrait of a Young Woman, 2nd century. Encaustic on wood. Louvre, Paris.

Michelangelo Buonarroti, The Sistine Chapel Ceiling, 1508–1512. Fresco. Vatican City, Rome.

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Delphic Sibyl (detail), 1508–1512. Fresco. Sistine Chapel, Vatican City.

Section III

Egon Schiele, Self-Portrait with Physalis, 1912. Oil on canvas. Leopold Museum, Vienna.

John Singer Sargent, Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose, 1885–86. Oil on canvas. Tate Britain, London.

Auguste Renoir, Bal du moulin de la Galette, 1876. Oil on canvas. Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

Willem de Kooning, Woman I, 1950–52. Oil on canvas. Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York.