Introduction

Monosodium glutamate (MSG) has long been a staple in Asian, particularly Chinese, cuisine. However, it has increasingly found its way into kitchens and restaurants around the globe. Known for its ability to enhance flavours and create the distinctive taste known as umami, MSG is both celebrated and vilified. Many chefs and food lovers praise it for the depth it brings to dishes. Others remain wary due to persistent myths and misconceptions about its health effects.

Personal Experience

Having lived in China for eight years and visited several Asian countries, I can attest to the omnipresence of MSG in Asian cuisine. From bustling street food markets to high-end restaurants, MSG is a ubiquitous ingredient that is difficult to avoid. The crystalline form of MSG is commonly added to food alongside salt. Many other forms of MSG, both synthetic and natural, are also integrated into the cuisine. Ingredients like soy sauce, tofu, seaweed, mushrooms, fish sauce, dried shrimp, dried scallops, and various broths all contribute to the umami richness that defines many Asian dishes.

In my own experience cooking Chinese food, I often used “chicken powder,” a granulated or powdered chicken broth, another source of MSG. This widespread use highlights how deeply MSG is embedded in these cultures’ culinary practices. Despite the myths and misconceptions still propagated about MSG, scientific studies show no specific reason why consumers should avoid it. MSG is generally recognized as safe for consumption within reasonable limits, except for the very rare cases where individuals are genuinely sensitive to it.

In this blog post, I’ll delve into the multifaceted world of MSG. I will explore its chemical nature, historical roots, and culinary applications. I’ll address the controversies and debunk some common myths surrounding its use, providing a balanced view backed by scientific evidence. Whether you’re a seasoned cook looking to enhance your dishes or a curious foodie eager to learn more, this comprehensive guide will shed light on everything you need to know about MSG and its role in the culinary arts.

What is Monosodium Glutamate?

Monosodium glutamate, commonly known as MSG, is a flavour enhancer that has been a cornerstone of culinary practices, particularly in Asian cuisine. Chemically, MSG is the sodium salt of glutamic acid, an amino acid that occurs naturally in many foods and is a building block of proteins. MSG was first discovered in 1908 by Japanese chemist Kikunae Ikeda, who was intrigued by the distinct savoury taste of seaweed broth. Ikeda isolated glutamic acid from the seaweed and found that it produced a stable and flavour-enhancing compound when combined with sodium. He named this taste “umami,” which is now recognized as the fifth basic taste alongside sweet, sour, salty, and bitter.

Understanding MSG’s chemical composition and historical context helps demystify its role in cooking. By enhancing the natural umami flavours in foods, MSG has become a valuable tool in kitchens worldwide.

Addressing the MSG Controversy

The Origin of MSG’s Controversial Reputation in the West

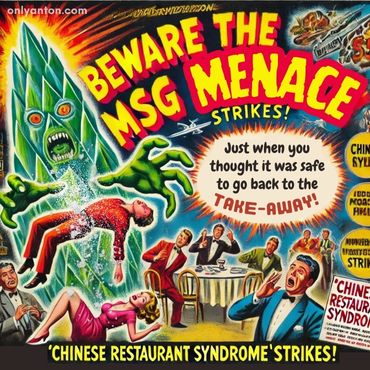

Monosodium glutamate (MSG) has long been a subject of controversy, especially in the West. This controversy traces back to a pivotal moment in 1968 when Dr. Robert Ho Man Kwok published a letter titled “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome” in the New England Journal of Medicine. In his letter, Dr. Kwok described experiencing symptoms such as headaches, palpitations, and numbness after eating at Chinese restaurants. He speculated that there may be a link between these symptoms and the presence of MSG in the food.

The term “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome” (CRS) quickly gained traction, leading to widespread suspicion and fear of MSG. Media coverage and anecdotal reports further amplified this phenomenon, often sensationalizing the potentially adverse effects of MSG consumption. Despite the lack of solid scientific evidence, the notion that MSG could cause a range of symptoms became deeply ingrained in public consciousness, particularly in the United States.

Changing Perceptions Over Time

In the decades following the initial controversy, scientific research has largely debunked the myths surrounding MSG. Numerous studies have found no consistent evidence to support the claims that MSG causes adverse reactions in the general population. Organizations such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the World Health Organization (WHO) have declared MSG to be safe for consumption.

However, the perception of MSG varies significantly across cultures. In many Asian countries, MSG is a common and accepted ingredient valued for its ability to enhance the umami flavour in dishes. In contrast, Western nations have been slower in embracing MSG due to the lingering stigma of the CRS controversy.

Re-evaluation

There has been a shift towards re-evaluating MSG with a more balanced perspective in recent years. Culinary experts and food scientists have advocated for the use of MSG, highlighting its safety and culinary benefits. The growing appreciation for umami as the fifth basic taste has also contributed to a more nuanced understanding of MSG’s role in cooking. Chefs and food enthusiasts are increasingly recognizing that, when used appropriately, MSG can enhance the overall flavour profile of a dish without negative health impacts.

Despite the progress in changing public perception, MSG continues to face some resistance. The negative associations and misconceptions persist, particularly among those who remember the initial scare of the late 20th century. Nevertheless, ongoing education and open discussions about the science behind MSG are helping to foster a more informed and accepting view of this flavour enhancer.

By understanding the history and evolution of MSG’s reputation, we can appreciate the complexities of food science and cultural perception. This knowledge encourages us to approach MSG with an open mind, recognizing its potential to enrich our culinary experiences without undue fear.

Debunking Myths About MSG

Myth 1: MSG Causes Headaches and Other Adverse Reactions

One of the most persistent myths about monosodium glutamate (MSG) is that it causes headaches and a range of other adverse reactions, collectively known as “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome” (CRS). This myth originated from anecdotal reports and a letter published in 1968, but scientific research has largely debunked these claims.

Numerous studies have investigated the alleged link between MSG and adverse symptoms. A review of the scientific literature by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) concluded that MSG is “generally recognized as safe” (GRAS) when consumed at customary levels. Controlled double-blind studies, where neither participants nor researchers know who is receiving MSG or a placebo, have failed to reproduce the symptoms attributed to MSG consumption consistently. The FDA and the World Health Organization (WHO) both consider MSG safe for the general population.

Myth 2: MSG is Unhealthy and Should Be Avoided

Another common myth is that MSG is inherently unhealthy and that consumers should avoid it. Scientific evidence does not support this belief. MSG is simply the sodium salt of glutamic acid, an amino acid naturally present in many foods, including tomatoes, cheese, and mushrooms. The human body metabolizes MSG in the same way it metabolizes naturally occurring glutamate in food.

Several comprehensive reviews and research studies have examined the safety of MSG. The Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) and the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) have both evaluated the available evidence and concluded that MSG is safe when consumed as part of a regular diet. The misconception that MSG is harmful often stems from misunderstandings about its chemical nature and its role in food.

Myth 3: MSG is a Synthetic Chemical Unlike Natural Glutamate

A common misconception is that MSG is a synthetic chemical, unlike the natural glutamate found in foods. In reality, the glutamate in MSG is chemically identical to the glutamate found in natural sources. Glutamic acid is an amino acid that occurs naturally in many protein-rich foods. It is a crucial component of human metabolism.

Manufacturing MSG involves fermenting starch, sugar beets, sugar cane, or molasses. It is a process similar to that used to produce other common food ingredients like vinegar or yogurt. This fermentation process yields glutamate, which is then purified and crystallized into MSG. The body does not distinguish between the glutamate derived from MSG and that from natural sources.

Scientific Evidence and Balanced View

Scientific research consistently supports the safety of MSG for the general population. While some individuals may report sensitivity to MSG, these cases are relatively rare and often not reproducible under controlled conditions. It is crucial to approach MSG with a balanced perspective, recognizing that it is a widely used and thoroughly studied ingredient.

For those concerned about MSG or who believe they may be sensitive to it, moderation and personal experience can guide their choices. However, it is essential to separate scientific fact from myth. It is equally important to understand that MSG, like many other food ingredients, can be part of a healthy and enjoyable diet when used appropriately.

By debunking these myths, we can appreciate MSG’s role in enhancing the umami flavour in foods. We can make informed decisions about its use in our cooking and dining experiences. This understanding helps us move beyond unfounded fears and enjoy the rich, savoury flavours that MSG can bring to our culinary adventures.

Health Considerations Regarding MSG

Sensitivities to MSG

While rare, some individuals may experience mild symptoms such as headaches or nausea after consuming MSG, known as MSG Symptom Complex. These reactions are typically short in duration and do not result in long-term health effects. Those who suspect they may be sensitive to MSG should consult healthcare professionals to tailor their diets.

Guidelines from Health Authorities

Health authorities such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the World Health Organization (WHO) have established guidelines to ensure the safe consumption of MSG. The FDA has classified MSG as “generally recognized as safe” (GRAS) when used according to good manufacturing practices. Similarly, the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) has conducted extensive reviews and concluded that MSG is safe when consumed at normal dietary levels.

The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has also reviewed the safety of MSG. They have set an acceptable daily intake (ADI) of 30 mg per kg of body weight. This guideline provides a reference point for safe consumption and helps individuals gauge their intake relative to their body weight.

Understanding the Connection Between MSG and Umami

The Concept of Umami: The Fifth Basic Taste

Umami is often referred to as the fifth basic taste, alongside sweet, salty, sour, and bitter. Umami was identified relatively recently in the context of Western scientific discovery. The term “umami” is Japanese, translating roughly to “pleasant savoury taste.” It describes a rich, mouth-filling sensation distinct from the other four basic tastes.

Umami’s discovery dates back to 1908. Kikunae Ikeda, a Japanese chemist, isolated glutamate as the compound responsible for the savoury taste in seaweed broth (kombu dashi). Ikeda realized that the traditional four taste categories did not account for this taste. He identified monosodium glutamate (MSG) as the critical component that elicited this unique taste and named it “umami.” After this discovery, MSG was commercialized as a flavour enhancer, rapidly gaining popularity in Japan and worldwide.

MSG and Its Relation to Umami

The connection between MSG and umami is fundamentally tied to the presence of free glutamates. When foods rich in glutamate break down through cooking, fermentation, or ripening, they release free glutamates, which our taste receptors recognize as umami. This process explains why aged cheeses, ripe tomatoes, and fermented soy products like miso and soy sauce are so flavourful.

Understanding the relationship between MSG and umami helps demystify why certain foods taste so satisfying and how MSG can replicate and enhance these flavours. Recognizing umami’s role in our taste perception underscores its importance in culinary traditions worldwide. It also validates the culinary practices that have utilized MSG for over a century.

Natural vs. Artificial Sources of MSG

Monosodium glutamate (MSG) can be found in both natural and synthetic forms and is crucial in enhancing the umami flavour in foods. Understanding the differences between these sources and their applications can help clarify the broader discussion around MSG in culinary practices.

Naturally Occurring Glutamates

Glutamates are naturally occurring amino acids found in a variety of foods. These naturally occurring glutamates contribute to the umami flavour, enhancing the taste profile of dishes without the need for added MSG. Some prominent examples include:

- Tomatoes: Tomatoes, particularly when cooked or sun-dried, are high in free glutamates, contributing to their rich, savoury flavour.

- Cheese: Aged cheeses, such as Parmesan and Roquefort, contain high levels of free glutamates due to the breakdown of proteins during aging.

- Seaweed: Kombu, a type of seaweed, is traditionally used in Japanese cooking to make dashi, a savoury broth. It was in kombu that Ikeda first identified glutamate.

- Soy Products: Fermented soy products like soy sauce, miso, and tofu are rich in umami, enhancing the flavours of many Asian dishes.

- Meat and Fish: These protein-rich foods are naturally high in glutamate, and their savoury flavours are intensified through cooking methods such as roasting and grilling.

- Mushrooms: Certain varieties, like shiitake, are rich in natural umami compounds.

- Fermented Fish Products: Fish sauce and Roman garum are traditional sources of natural glutamates.

These foods have been used for centuries to enhance flavours, long before the discovery and synthesis of MSG.

Synthetic MSG

Synthetic MSG is produced through fermentation using starch, sugar beets, sugar cane, or molasses. This industrial process creates a purified form of glutamate, which is then combined with sodium to form MSG crystals. Synthetic MSG is used as a seasoning and flavour enhancer in various packaged foods and restaurant dishes.

Common Brands and Names:

- Accent: A popular brand of flavour enhancer in the United States.

- AJI-NO-MOTO: A globally recognized brand of MSG, widely used in Asia and other parts of the world.

- Kagaku Choumi-ryou (Japanese): The term translates to “chemical seasoning.”

- Weisu/Weijing (Mandarin): Common terms used in Chinese-speaking regions.

- Mecin/Micin (Indonesian): Terms used in Indonesia for MSG.

- Mi Wong (Korean): A commonly used term in Korea.

- Pong Churod (Thai): The term used in Thailand.

Understanding the sources and uses of natural and synthetic MSG helps demystify its role in culinary practices. Whether derived from tomatoes, cheese, or seaweed or synthesized in a lab, glutamates play a fundamental role in creating the rich, savoury flavours we associate with umami. This knowledge can empower cooks and consumers to make informed decisions about incorporating umami into their culinary repertoire. We can also appreciate this powerful flavour enhancer’s historical and scientific context.

Understanding Autolyzed and Hydrolyzed Ingredients

When navigating the world of food labels, you might come across terms like autolyzed yeast extract, hydrolyzed vegetable protein (HVP), or carrageenan. These ingredients, often found in processed foods, contain free glutamates similar to those in MSG.

Autolyzed Ingredients: Autolyzed yeast extract is a common example of an ingredient in which naturally present enzymes break down proteins into amino acids, including glutamic acid. This process enhances the flavour profile of foods, making them more savoury and umami-rich. You’ll find autolyzed yeast extract in soups, sauces, and snack foods.

Hydrolyzed Ingredients: Hydrolysis involves breaking down proteins using acids or enzymes, resulting in a mixture of amino acids, including glutamate. Hydrolyzed vegetable protein (HVP) and hydrolyzed soy protein are frequently used in processed foods to boost flavour.

Other Sources of Free Glutamates: Carrageenan, derived from seaweed, and sodium caseinate, a milk protein derivative, are also used in the food industry. While they don’t directly contain glutamates, they are often found in products that do.

Understanding these ingredients is crucial for those with sensitivities to free glutamates. Reading labels carefully and being aware of these terms can help manage the dietary intake of glutamates and avoid adverse reactions.

Advice on Using MSG and Enhancing Umami in Cooking

Incorporating MSG into home cooking can be a great way to enhance the flavour of your dishes, but it’s important to use it wisely to achieve the best results. Here are some tips and strategies for safely incorporating MSG and balancing flavours to enhance umami without over-reliance on added MSG.

Tips

- Use MSG Sparingly: Generally, 1/4 to 1/2 teaspoon of MSG is enough for a dish that serves four to six people. Start with a small amount and adjust according to taste.

- Combine with Other Seasonings: Use MSG with herbs, spices, and other flavour enhancers to create a balanced and flavourful dish.

- Timing: Add MSG towards the end of the cooking process to allow it to dissolve fully and integrate into the dish.

- Pair with Umami-rich Ingredients: Combining MSG with naturally umami-rich ingredients like tomatoes, mushrooms, soy sauce, and cheese can amplify the overall flavour of the dish.

- Layering Flavours: Build complexity in your dishes by layering umami-rich ingredients at different cooking stages. For example, start with a base of sautéed onions and garlic, add tomatoes and mushrooms, deglaze with soy sauce or fish sauce, and finish with a sprinkle of Parmesan.

- Fermented Ingredients: Use fermented products like miso, kimchi, and sauerkraut. These add umami and introduce beneficial probiotics and complexity to your dishes.

- Balancing Flavours: Ensure that your dish balances the five basic tastes: sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami. This balance can prevent the dish from becoming overly salty or overwhelmingly savoury. For instance, a splash of vinegar or a squeeze of lemon can brighten and balance a rich, umami-heavy stew.

By understanding the various sources of umami and utilizing them effectively, you can create profoundly flavorful and satisfying dishes. Incorporating MSG and other umami-enhancing techniques can elevate your cooking, allowing you to enjoy richer, more complex flavours in every meal.

Navigating MSG and Umami When Dining Out

When dining out, especially in authentic Chinese eateries or restaurants abroad, navigating the use of MSG can be a challenge. Here are some practical tips for inquiring about MSG in your food and enjoying umami-rich dishes safely, especially if you have sensitivities.

Advice

- Ask Directly: Don’t hesitate to ask the staff if their dishes contain MSG.

- Explain Your Sensitivity: If you are sensitive to MSG, explain this to your server or the chef.

- Look for Clues on the Menu: Some menus will indicate if dishes contain MSG.

- Choose Fresh Ingredients: Opt for dishes that are likely made from fresh ingredients, such as steamed vegetables and grilled meats.

- Trust Your Senses: If the food tastes excessively savoury or if you feel the onset of symptoms, it might be wise to stop eating and choose another dish.

- Identify Natural Umami Sources: If you have sensitivities, seek out dishes made with natural umami-rich ingredients like tomatoes, mushrooms, seaweed, and aged cheeses. These foods provide the umami flavour without the potential side effects of added MSG.

- Communicate Clearly: Learning a few key phrases in the local language can be extremely helpful when travelling abroad. Phrases like “I am allergic to MSG” or “Can you make this without MSG?” can go a long way in ensuring your dietary needs are met. For example, in Mandarin, you can say “我对味精过敏” (Wǒ duì wèijīng guòmǐn), which means “I am allergic to MSG.”

- Carry Translation Cards: If you have severe sensitivities, consider carrying translation cards that clearly state your dietary restrictions. You can show these cards to restaurant staff to help communicate your needs.

- Research Restaurants in Advance: Look up reviews and menus online before choosing a restaurant. Websites and apps like Yelp, TripAdvisor, and local food blogs often provide information about whether restaurants use MSG.

- Trust Your Senses: If you are particularly sensitive, trust your senses. If the food tastes excessively savoury or if you feel the onset of symptoms, it might be wise to stop eating and choose another dish.

- Allergy-Friendly Establishments: Some restaurants specialize in allergy-friendly or health-conscious cuisine. These establishments often avoid using additives like MSG, which can be a safer choice for those with sensitivities.

Conclusion

In this blog post, I explored the multifaceted world of monosodium glutamate (MSG), its role in culinary practices, and its controversies. Understanding the connection between MSG and umami and recognizing the difference between natural and artificial sources of glutamates allows us to appreciate the complexity and depth of flavours in our food. By incorporating MSG mindfully and exploring natural umami enhancers, we can elevate our culinary experiences while maintaining a balanced and health-conscious approach.

What About You?

I’d love to hear from you! Share your thoughts and experiences with MSG and umami in your cooking or dining adventures. Have you experimented with using MSG at home? How do you enhance umami flavours in your dishes? Have your perceptions of MSG changed after reading this article? Your insights can help fellow readers explore and appreciate the diverse world of culinary flavours.

Join the Conversation

Please share your comments below and engage with our community of food enthusiasts. Here are a few questions to start the conversation:

- Have you noticed a difference in flavour when using MSG in your cooking?

- What natural umami-rich ingredients do you love to use in your recipes?

- Have you experienced any sensitivities to MSG, and how do you manage them?

Further Reading and Resources

Related Blog Posts on Only Anton

- Sichuan Cuisine: A Culinary Odyssey in Chengdu: Dive into the world of Sichuan cuisine, known for its bold flavours and unique use of spices. This post explores the key ingredients and techniques that make Sichuan food distinct.

- Cha Chaan Teng: Hong Kong’s Diner Food: Discover the unique charm of Hong Kong’s Cha Chaan Tengs, offering a blend of Eastern and Western culinary influences. Learn about their history, popular dishes, and cultural significance.

The following resources will provide a well-rounded understanding of MSG, its uses, and the science behind its effects, enhancing your knowledge and appreciation of this controversial yet widely used ingredient.

Books

- Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat: Mastering the Elements of Good Cooking by Samin Nosrat: Explores the fundamental elements of cooking, including the role of umami and flavour balance. Watch the series on Netflix, read it online, find it at a library, or buy it here.

- Umami: The Fifth Taste by Kanami Tsuno: A deep dive into the science and culinary applications of umami.

- Umami: Unlocking the Secrets of the Fifth Taste, by Ole Mouritsen and Klavs Styrbæk: A deep dive into the science and culinary applications of umami. Find it online, in a library, or buy it here.

- The Food Lab: Better Home Cooking Through Science by J. Kenji López-Alt: Provides scientific insights into cooking techniques, including how to use MSG and other umami enhancers. Find it at a library or online, or purchase it here.

Articles and Blog Posts

- “MSG Is Finally Getting Its Revenge,” by Yasmin Tayag, The Atlantic (May 2023): An informative article detailing the history and controversy surrounding MSG. Follow the link here.

- “Is MSG Truly Unhealthy? All You Need to Know” by Ariane Lang, Healthline (February 2023): Examines common myths and scientific evidence about MSG’s health effects. Read more about it here.

Encyclopedic Entries

Reputable Websites

- Food Insight: MSG: Food Insight is the information hub of the International Food Information Council (IFIC). Find information about MSG on the website here.

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Check the link here.

- Umami Information Center: Follow this link.

- ScienceDirect: Articles on MSG: For information about MSG, visit the site here.